The priceless relic could be at the bottom of a lake … or in somebody’s attic – Theories abound.

By Seanna Adcox

SCDailyGazette.com

COLUMBIA

Call it South Carolina’s “National Treasure” mystery — except, in this true caper, the lost relic’s existence was never in doubt, and there is no hidden map with clues on its location. At least, not that anyone’s discovered since it went missing nearly 83 years ago.

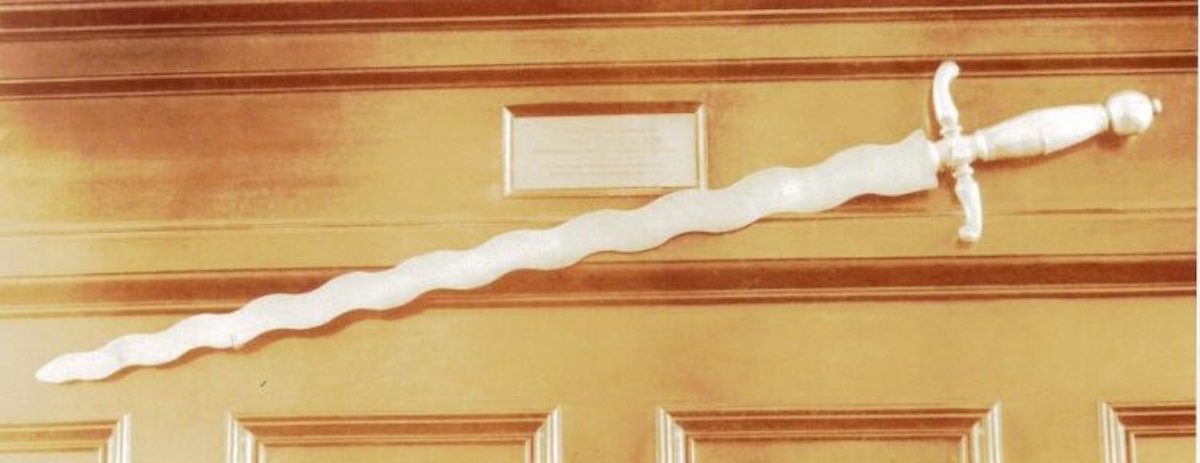

How South Carolina’s original sword of state, which dates to at least 1704, disappeared remains the subject of speculation and Statehouse legends.

Theories range from the simple – that a tourist snatched it from the Senate dais, shoved it down a pants leg, and walked out with the hilt hidden under a coat — to the absurd. The 5-foot sword with a snakelike blade, reminiscent of the flaming sword in Genesis guarding the tree of life, was stolen by Nazi sympathizers obsessed with the occult, one story goes. After all, it was 1941.

“We’re getting way out there, but there are tons of theories because nobody knows,” said Charles Reid, clerk of the South Carolina House.

Compounding the conspiracy theories is that the theft seemed to go largely unnoticed at the time. No police report exists. The official Senate journals contain just a couple of mentions. The longest records the presentation a month later, in March 1941, of a temporary replacement from the Charleston Museum.

Was it a practical joke on the part-time sergeant-at-arms, a barber, that went too far? Did a powerful-yet-disliked senator take it as a concession after he was forced out?

Depending on the tale, the sword may be rusting away at the bottom of what’s now Lake Wateree. It might be buried in a concrete vault with the long-dead thief. It might be secreted away in a Masonic lodge somewhere in the state.

Or “it could be sitting in grandma or grandpa’s attic somewhere, and they don’t know what they have,” Reid said.

Clerk since 2004, Reid probably knows more about the sword than any living person. But after researching various rabbit trails to literal and figurative dead ends, he stresses that almost everything about the sword remains an enigma.

Still, professional historians and history buffs, including Reid, hold out hope that the priceless, silver-handled sword will eventually be returned.

Other missing artifacts found

They can look to South Carolina’s northern neighbor for encouragement.

In 1865, a Union soldier stole North Carolina’s then-76-year-old copy of the Bill of Rightscas a souvenir from the occupied Capitol, then sold it for $5 when he got home to Ohio. It remained in the same family for 134 years before a Connecticut antiques dealer bought it and tried to resell it, resulting in the FBI seizing the document in Philadelphia in 2003. It was returned to North Carolina two years later.

“That’s an example of how something can be kept in one family and passed down,” said Eric Emerson, director of the South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

The sword “could be in somebody’s house even today,” he added, speculating that maybe it will show up on some future episode of “Antiques Roadshow.”

It also wouldn’t be the first stolen symbol of power to be returned to the Statehouse.

The South Carolina Mace, the emblem of authority for the House, has gone missing twice, the first time for roughly 40 years.

During the Revolutionary War, it was hidden out of fear that Loyalists in Charleston — then the state capital — would steal it.

“It was hidden so well, the people who hid it either died or forgot where it was,” Reid said.

It turned up in 1819, after former Charleston Congressman Langdon Cheves became president of the Second National Bank of the U.S. and found it in a vault in Philadelphia.

It disappeared again in 1971 and was recovered 21 days later in Florida by the chief of the State Law Enforcement Division.

A former Statehouse security guard stole the mace after he was fired for being drunk on the job, Reid said. When he turned up in a Veterans Affairs hospital with a mental breakdown, then-Chief Pete Strom took the state plane down to Gainesville, used a crowbar to open the ex-guard’s car, grabbed the mace and flew back to Columbia, according to news accounts at the time and SLED documents.

Since 1998, when the Legislature moved back into the Statehouse following a renovation, the mace has rested in a bombproof, bulletproof glass safe on the back wall of the House. A key and combination are needed to access it. Reid says he neither has nor wants either.

As with the Senate’s replacement sword of state, when the mace is put on its rack at the start of each legislative day, the lights on the rostrum light up. It signifies that the lawmaking body is in session. (The sword in use since 1951 was a gift to South Carolina from Lord Halifax, then the British ambassador to the U.S.)

The mace, made in London in 1756 and bought by the colonial South Carolina Assembly, is the nation’s oldest symbol of state legislative authority still in use. Made of silver and covered in gold, the mace is a beautiful work of art, Reid said.

“But if our sword was still here, it would be older,” he added.

Mysterious origins, too

According to the earliest records, the sword was bought by the Commons House of Assembly — the only elected branch of the colonial government — for the appointed governor in 1704 for 26 British pounds, the equivalent of about $6,000 today. In 1776, after South Carolina first adopted an independent state constitution, the newly elected president of the Senate was escorted to the chamber by the Charleston sheriff carrying the sword.

The ceremonial sword has preceded senators on state occasions ever since. At some point, a Senate sergeant at arms replaced the sheriff.

Beyond that, even its origins are a mystery. According to the official history written after it disappeared and still printed in the annual legislative manual, the sword was made by a Charleston silversmith. But historians agree that’s probably bunk, as there were only two silversmiths in Charleston at the time, and neither had the expertise for such a complex sword, according to Reid and experts he corresponded with during his research.

The thinking is that it was probably made in Germany, where the flaming, or wavy, blade originated. It may have already been old when purchased in 1704. Or, it may have been a replica. There’s no way to know, Reid said.

Regardless, it’s a priceless piece of South Carolina’s history that should be returned — if it still exists. The mystery is what’s so intriguing, he said.

“Everybody wants a mystery to be solved,” he said. “It’s something we should know more about. The fact that we don’t leads to all the speculation of ‘what if,’ ‘what could be.’”

And while the speculation can be fun, he added, there’s also a serious reason why people should care.

“South Carolina has a history unlike any other state. It’s a history of so many highs and so many lows that it’s important to remember that there are some symbols that still tie us to who we were and will hopefully take us on to who we’re becoming.”

Seanna Adcox is a South Carolina native with three decades of reporting experience. She joined States Newsroom in September 2023 after covering the S.C. Legislature and state politics for 18 years. Her previous employers include The Post and Courier and The Associated Press.