By Skylar Laird

SCDailyGazette.com

COLUMBIA — Civil War hero Robert Smalls could one day stand just outside the Statehouse visitors’ entrance, clad in the three-piece tuxedo he would have worn while serving in Congress, a legislative panel decided Wednesday, Jan. 8.

Smalls, who escaped slavery on a Confederate steamship and later served in the Statehouse and Congress, will be the first individual Black person recognized on the Statehouse grounds. Another monument represents the story of Black South Carolinians, but it doesn’t identify any specific people.

The plan still needs approval from a full committee, as well as the House and Senate. If the unanimous votes Wednesday, as well as unanimous approval of the legislation to honor him with a monument, are any indication, the proposal will have little trouble reaching the finish line.

The law placing a monument on the grounds includes only one deadline: The commission needed to decide on a design and location by Jan. 15, which it accomplished with a week to spare. As for construction, the law requires only that it happen “as soon as is reasonably possible” after the full Legislature approves the plans.

That gives legislators time to finalize details, such as the size and material of the statue, and raise as much money as possible, said Rep. Brandon Cox, the Goose Creek Republican who co-sponsored the law with Rep. Jermaine Johnson, D-Columbia.

“This isn’t going to be done haphazardly,” Cox told reporters. “Two hundred years from now, when we’re looking at the Statehouse grounds, that statue will still be up there.”

Location

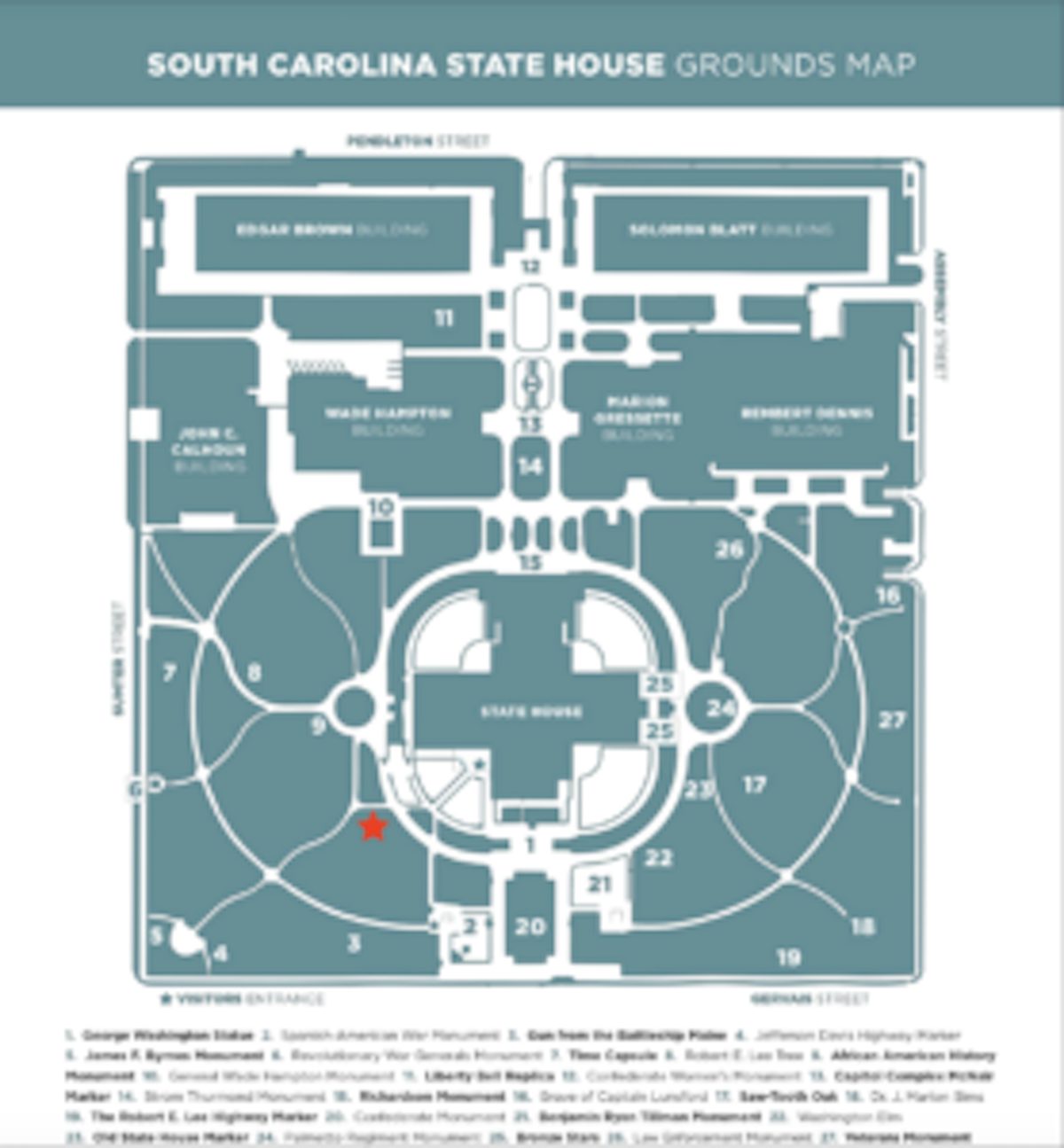

The monument will stand straight across from the visitors’ entrance to the Statehouse, situated between the Spanish-American War Monument and the African American History monument.

With more than two dozen statues and markers of various sizes already in place across the Statehouse grounds, finding a suitable piece of land that didn’t crowd any other statues or add too much weight to the underground parking garage posed a potential challenge.

But a spot opened up in April 2023, when crews finished removing a dead tree, Johnson said.

“Whether this might have been divine intervention in preparation of this, I’m going to let you all decide on that,” he said.

The monument will be in full view of any visitors walking into the Statehouse. Among them are the school children often dropped off on the nearby Sumter Street, Johnson said.

From Smalls’ monument, those of Confederate general and former Gov. Wade Hampton and former Gov. Benjamin “Pitchfork” Tillman will be visible, which is fitting since all three men were in politics at the same time, Johnson said.

Smalls and Tillman, in particular, had a contentious relationship. Tillman, a white supremacist who advocated for killing Black people who tried to vote, led the group that in 1895 rewrote the state constitution that Smalls had helped write 27 years earlier. Tillman’s version, which is still in place today, rolled back education and voting rights that Smalls had fought to include in the constitution that allowed South Carolina to rejoin the Union.

Design

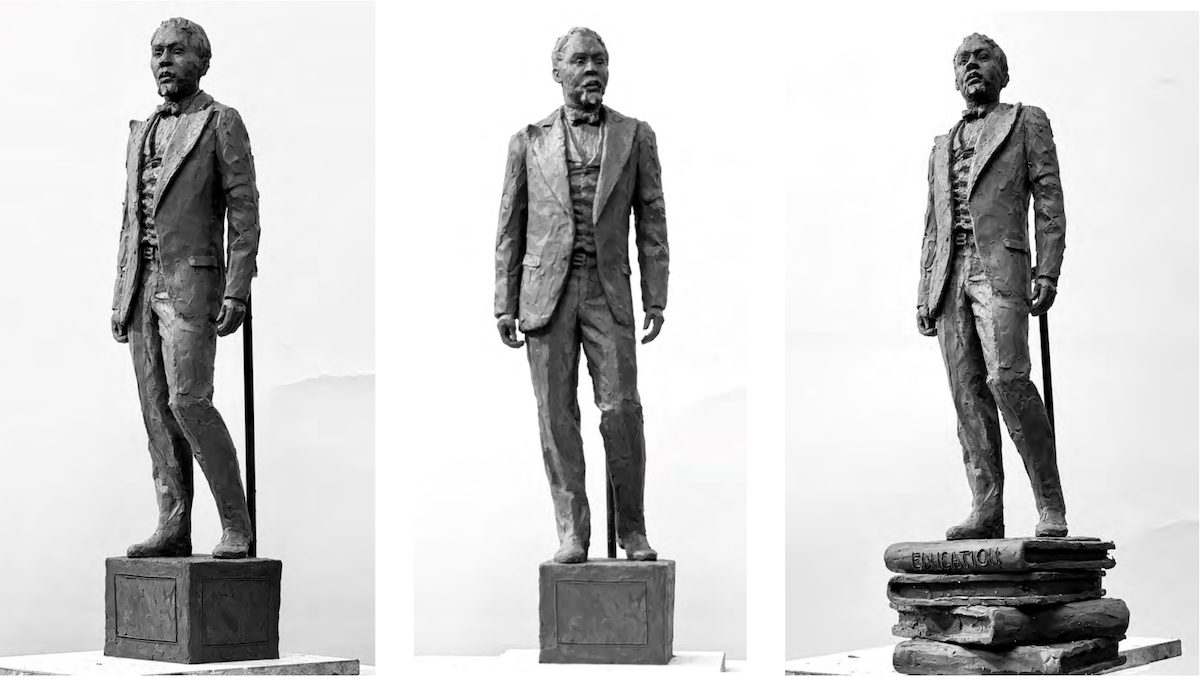

The monument’s depiction of Smalls in a three-piece tuxedo, as he often wore in Congress, was approved over two other designs that showed more of his history because of the winning model’s similarity to other statues on the Statehouse grounds, members of the 11-person commission said.

Six artists submitted proposals for sculptures. Commission members asked three to create models of their monument ideas before narrowing that down to a favorite.

The final design, by Atlanta-based Basil Watson, is a traditional full-body sculpture reminiscent of those on the grounds already, including that of Tillman. Depicting Smalls in the same way shows that he was equal among historic figures, Johnson said.

“He needs ‘no special defense,’” Johnson told reporters, referencing a famous quote by Smalls. “Put him up there as an equal to everyone else.”

Watson was struck by Smalls’ dedication to public, compulsory education throughout his lifetime, he told the Daily Gazette. One of the two sample designs Watson submitted has Smalls standing on a stack of books.

The Atlanta-based artist also created the monument unveiled on the University of South Carolina campus last year honoring the first Black students admitted to the school after Reconstruction. Other public figures Watson has commemorated in sculptures include Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Usain Bolt.

The Smalls monument appealed to him because of how inspiring Smalls’ story is, Watson said.

“He demonstrated from an early age a spirit of demanding equality, feeling that he was equal and capable,” Watson said. “I think this was the spirit that he carried throughout his life.”

Another design by Florence-based Brown Memorials, which shows three versions of Smalls throughout his life, piqued Sen. Chip Campsen’s interest. The Isle of Palms Republican suggested that the committee consider it for the final design because it tells more of Smalls’ story without needing a person to read the plaque.

Visitors are “not going to necessarily have someone to interpret the history of who Robert Smalls was, what he did, the things he overcame, the grace he demonstrated to those who even had enslaved him previously,” Campsen said.

Mike Shealy, who chairs the commission, had the same thought when first looking through the designs, but he realized upon further thought that some visitors, such as his 10-year-old grandson, might not understand that the three people on the Brown Memorials design are all meant to be one man, he said.

The simpler sculpture of Smalls would likely be easier for visitors to understand upon first glance, said Shealy, who oversees special projects for the state Department of Administration.

“I think the simplicity of a statue of one man on a pedestal who is equal to other people that are memorialized on our Statehouse grounds is the best depiction,” said Shealy, formerly the Senate’s longtime budget director.

Smalls’ story

The committee suggested a series of facts to include on the panel beneath Smalls’ feet to educate onlookers, including his dates of birth and death, the years he served in office, and details of his story.

Born into slavery in Beaufort, Smalls was sent to Charleston in 1851 at age 12. Twelve years later, in 1862, Smalls hijacked the steamship Planter, on which he was an enslaved crew member, and steered himself, other slaves and their family members past Confederate troops to safety.

Smalls became the first Black man to pilot ships for the U.S. Navy, eventually captaining the Planter for the Union. Congress awarded him prize money for capturing the Planter, allowing him to later buy the mansion in which he had once been enslaved.

During Reconstruction, Smalls was part of a convention of delegates who wrote the state’s 1868 constitution. That constitution, which resulted in Congress readmitting South Carolina as part of the United States, promised free education to all children and voting rights to all men.

After serving in both the House and Senate, Smalls won election in 1874 to Congress, where he served five terms. He again joined delegates rewriting the state constitution in 1895, where he pleaded for “fair and honest” elections, knowing the authors intended to pull back rights for Black voters.

One side of the panel could include a quote from a speech Smalls gave at that convention, which is also etched on his gravesite in Beaufort, Johnson suggested.

“My race needs no special defense, for the past history of them in this country proves them to be the equal of any people anywhere,” he said in his speech. “All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.”

Funding

With a design and location chosen, legislators and the state Department of Administration will begin fundraising in earnest.

How much they need to raise, though, remains up in the air.

No official estimate has been made as to the final cost, Cox said. Legislators are hoping to raise money first to determine what material they can afford to use in constructing the sculpture and what size they could make it.

Some donations have come in, though legislators said they didn’t know how much. People are already enthusiastic about donating to the project, so funding shouldn’t be an issue, Cox and Johnson said.

The goal is “as much as we can raise,” Cox said.

Skylar Laird covers the South Carolina Legislature and criminal justice issues. Originally from Missouri, she previously worked for The Post and Courier’s Columbia bureau. S.C. Daily Gazette is part of States Newsroom, the nation’s largest state-focused nonprofit news organization.

Related Links