By Corrie Pelc

There is a distinct connection between diabetes and heart disease. Diabetics are twice as likely to have heart disease or a stroke. Because of this correlation, much research is now centering around a person’s cardiometabolic health, which refers to both heart conditions and metabolic conditions such as diabetes that affect a person’s metabolism.

Previous studies have examined the impact of different lifestyle modifications such as diet, exercise, and sleep on improving a person’s cardiometabolic health.

Now, researchers from the Cardiovascular Nutrition Lab at the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University suggest a person’s genetic preference toward different tastes may impact their overall food choices, resulting in an influence on their overall cardiometabolic health.

The researchers presented the study at Nutrition 2022, the annual meeting of the American Society for Nutrition.

How does our sense of taste work?

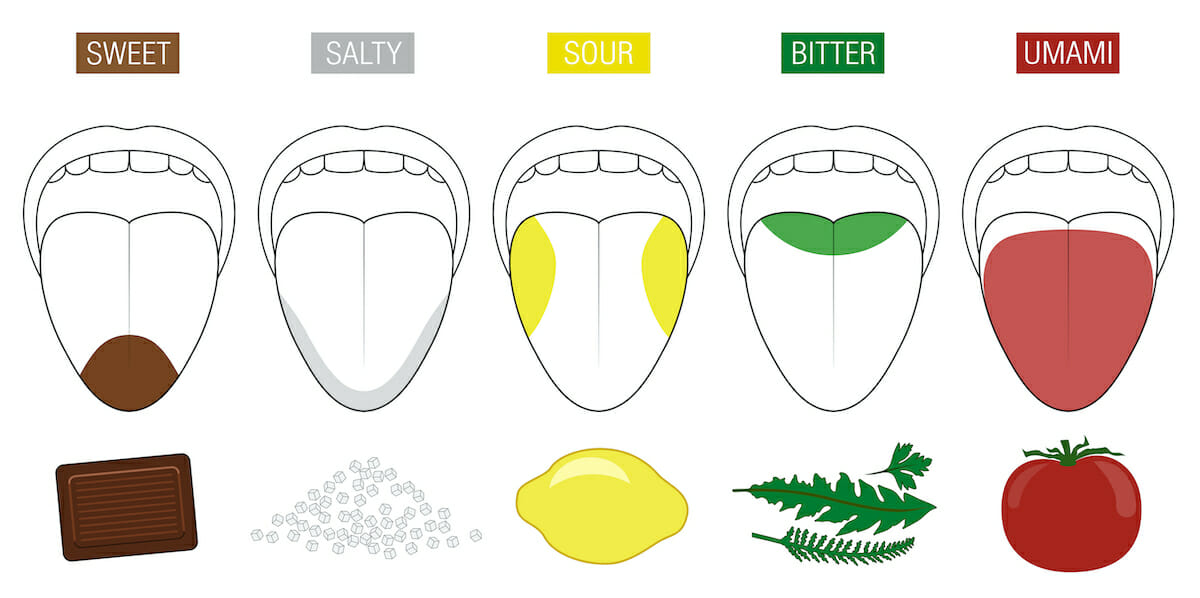

A person’s ability to taste different foods and beverages starts with the taste buds located on their tongue. On average, the human tongue has between 2,000 to 4,000 taste buds. On the tips of each taste bud are taste receptors. These help a person distinguish between five main tastes: sweet, sour, bitter, salty, umami.

Past research has looked at how a person’s sense of taste impacts their risk for obesity and Type 2 diabetes and how obesity in turn impacts taste.

Taste-related genes and cardiometabolic health

For this new research, Julie E. Gervis, the lead author of this study, said researchers wanted to look at why people find it difficult to make healthy food choices, and therefore increase their risk for diet-related chronic diseases. They also wanted to examine why people do not always eat what is good for them but eat what tastes good to them. “We wondered whether considering taste perception could help make personalized nutrition guidance more effective, by leveraging drivers of food choices and helping people learn how to minimize their influence. And since taste perception has a strong genetic component, we wanted to understand how taste-related genes were involved’.

The researchers found a correlation between a person’s polygenic taste score and the types of foods they chose. For example, the research team documented those with a higher bitter taste score consumed almost two servings less of whole grains each week than those with a lower bitter taste score. And those with a higher umami score ate fewer vegetables, especially red and orange ones, than those with a lower umami score.

They also found links between polygenic taste scores and certain cardiometabolic risk factors. For example, researchers reported participants with a higher sweet score tended to have lower triglyceride levels than those with a lower sweet score.

Personalized nutrition guidance

When asked how these findings might aid healthcare professionals in providing nutritional guidance to patients with diet-related diseases, Gervis said that as these findings are preliminary, the next step is to replicate these findings in independent cohorts to confirm their validity.

“My hope is that clinicians will be able to leverage our understanding of how taste-related genes impact food choices, to provide more effective personalized nutrition guidance,” she explained.

How the findings may be used

Gervis said their ultimate goal was to help people understand why they made certain food choices, and how they could use this information to equip them with more control over their diet quality and cardiometabolic health. “For example, if individuals who are genetically predisposed to have high bitter perception eat fewer whole grains, it might be recommended that they add certain spreads or spices or choose other types of foods that better align with their taste perception profile.”

Source: https://www. medicalnewstoday.com/articles/your-taste-genes-might-determine-what-you-like-to-eat-and-your-health; Fact checked by Harriet Pike, Ph.D., June 20, 2022.