By Wells Fargo Advisors

Investors may like to think they’re completely rational in their decision-making, but that’s highly unlikely. We don’t stop being human beings when it comes to investing, so psychology and emotions are apt to play roles—sometimes large ones—in the choices we make.

Behavioral finance studies investors’ real-life behavior and common biases. It considers the roles emotions and psychology play in making financial decisions and aims to identify factors that cause investors to sometimes act irrationally.

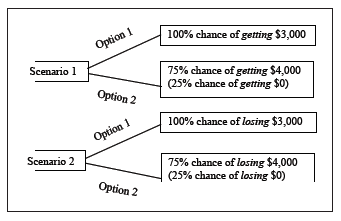

A key concept in behavioral finance is “prospect theory,” which describes how investors make decisions involving risk and gain. Studies have shown people frequently consider losses far more undesirable than they find comparable gains desireable. For example, take the following scenarios:

Given the first scenario, most people will avoid the risk and take option one (the sure $3,000 gain). On the other hand, when presented the second scenario, most favor option two (the 75% chance of losing $4,000) because it offers the possibility of avoiding the pain of a loss.

Keep in mind – and this is important – all four choices are mathematically equivalent. This means individuals’ responses were based primarily on their emotional reactions to fear of loss vs. enjoyment of gain, not rational decision-making.

The psychology of

risk and reward

If you ever wonder why markets sometimes act in ways that defy logic, behavioral finance helps explain it.

For example, bubbles can form when prices rise based on investors’ emotional reactions rather than the fundamentals. Once their sentiment eventually changes, a precipitous sell-off can follow.

Take what’s come to be known as the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s. Soon after the internet’s introduction, investors realized its potential to transform our everyday lives (which it clearly has). What they were over-optimistic about were internet-based companies’ abilities to quickly create profitable businesses.

In response to investors’ enthusiasm, the NASDAQ Index, where many of these companies’ stocks were listed, rose 189% during the two years leading up to its peak in March 2000. Perhaps more significantly, the price/earnings (P/E) ratio—a measure commonly used to determine how expensive stocks are (the higher the ratio, the more expensive stocks are considered to be)—was 175. By comparison, it was only approximately 24 at the end of 2020.

That suggests many investors were caught up in the furor over the New Economy and ignored the fundamentals. When investors realized it would be a long time before many of these companies became profitable, the bubble burst and stock prices plummeted.

The lesson for investors is the importance of being diversified and investing primarily based on fundamentals—not on emotion and the fear of missing out on the next “big thing.” Of course, diversification strategies do not guarantee investment returns or eliminate the risk of loss.

This article was written by/for Wells Fargo Advisors and provided courtesy Katie C. Phifer, CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™, RICP® and Vice President-Investments in Beaufort, SC at 843-982-1506.

Investments in securities and insurance products are: NOT FDIC-INSURED/ NOT BANK-GUARANTEED/MAY LOSE VALUE

Wells Fargo Advisors is a trade name used by Wells Fargo Clearing Services, LLC, Member SIPC, a registered broker-dealer and non-bank affiliate of Wells Fargo & Company.

©2021 Wells Fargo Clearing Services, LLC. All rights reserved. CAR: 0521- 01326