By Alan Schuster

Written at his creative peak, Czechoslovakian composer Antonin Dvorak’s “Rusalka” matches the same high quality of his finest orchestral works. Eventually, its popularity surpassed the best operas of his two most famous Czech mates, Smetana’s “The Bartered Bride” and Janacek’s “Jenufa.” Czechs were quick to embrace it, benefited in part by the fairy tale — Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Mermaid” — upon which the opera is based.

Today, the best reason to explain the belated popularity of “Rusalka” can be attributed to the extraordinary talents of the Met’s house diva, lyric soprano Renee Fleming. She has made Rusalka her signature role by headlining each of the Met’s three most recent revivals in 2004, 2007, 2009 — and this one makes it four.

“Rusalka” Act 1: A meadow by the edge of a lake: Three wood-sprites tease the Water Goblin, ruler of the lake. His daughter, Rusalka, tells him that she is in love with a human prince who comes to hunt around the lake, and she wants to become human to embrace him. He tells her it’s a bad idea, then steers her to a witch, Ježibaba, for assistance. Rusalka sings her Song to the Moon, asking it to tell the prince of her love. Ježibaba tells Rusalka that if she becomes human, she will lose the power of speech and that, if she is betrayed by him, both will be eternally damned. Rusalka agrees to this and drinks a potion. The prince, while hunting, finds Rusalka, embraces her, and leads her away, even though she is unable to speak.

Act 2: The prince’s garden: A gamekeeper and his nephew learn that the prince is to marry a mute. They suspect witchcraft as the prince is already lavishing attentions on a foreign princess who is a wedding guest. The princess, jealous, curses the couple. The prince rejects Rusalka. The princess, having won the prince’s affection, now scorns it.

Act 3: A meadow by the lake: Rusalka asks Ježibaba for a solution to her woes and is told she can save herself if she kills the prince with the dagger she is given. But Rusalka throws the dagger into the lake, turning her into a spirit of death living in the lake. The Gamekeeper consults Ježibaba about the prince, who, they say, has been betrayed by Rusalka. The Water Goblin says that it was actually the Prince that betrayed Rusalka. The Prince comes to the lake, and calls for Rusalka. He asks her to kiss him, knowing it means death and damnation. They kiss, he dies and Rusalka returns to the depths of the lake. (Thank you, Google.)

The music: Rusalka’s score is extensive, ranging from folk-inspired to grandiosity, and from the impressionism expressed in several nature motifs. And among those whose music must have influenced Dvorak were three contemporary composers, each of whom are subtly revealed in the first act. The opening scene with the wood-sprites at play by the lake brings to mind Wagner’s Rhinemaidens, even with their opening lines. For the sprites, it’s “Hoa! Hoa! Hoa!” For the maidens, it’s “Weia! Waga! Woge!”

And while Bizet’s clear and resonant style might be apparent, it’s Tchiakovsky’s Letter Scene from “Eugene Onegin” that is so thrillingly captured in Rusalka’s beseeching Plea to the Moon. Both are rich in melody, expressing similar sentiments with emotional outbursts.

A most unusual performance occurs during the last moments of the first act and continues through much of the second. Although Rusalka has become mute, she still spends considerable time on stage, acting and reacting to moments of joy, sorrow and remorse — and all without singing a single note. It’s got to be one of an opera diva’s most challenging tests, perfectly suited for Fleming. But the act still has its fine moments in the wedding scene, accompanied by Dvorak’s finely-tuned ballet music and some dramatic moments between the prince and the foreign princess. And, of course, Rusalka finally joins in near the end.

If the Moon Song wasn’t so sublime, then Rusalka’s beautiful aria in the third act — “I am torn from life” — would be a stunning alternative. In it, she touchingly expresses her separation from her sisters and the prince. But in the finale, they come together for an ecstatic duet in what one respected opera buff considered to be “twelve of the most glorious minutes in all of opera.” (At the least, it should rank as opera’s greatest kiss of death.)

Undecided about seeing “Rusalka”? This might help: Google “Renee Fleming, Song to the Moon,” then click the video image of the harp.

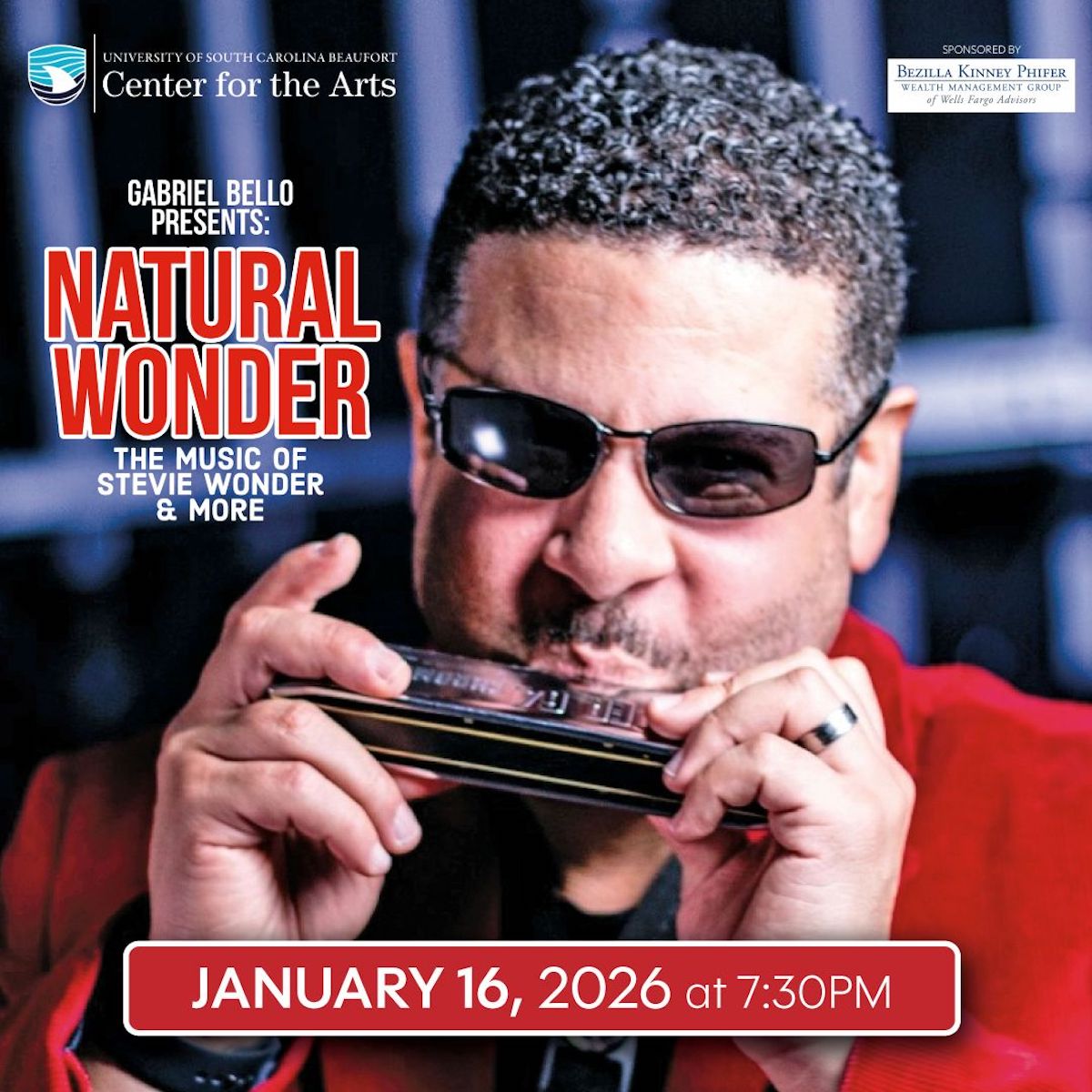

Three top-notch singers will join Fleming on stage — mezzo-soprano Dolora Zajick (Jezibaba), tenor Piotr Beczala (Prince) and bass-baritone John Relyea (Water Goblin) — when “Rusalka” is shown at the USCB Center for the Arts on Saturday, Feb. 8.

Tickets for adults are $22; OLLI members $18; Students $15. All seats assigned. The box office opens at noon for the 12:55 curtain time, or call 521-4145.