By Becky Sprecher

For The Island News

I’ve seen a lot of wild things on the opera stage, from duels, shootings and stabbings to Tosca leaping from a castle parapet to her death, John the Baptist’s head being brought in on a tray, and the burning of Valhalla.

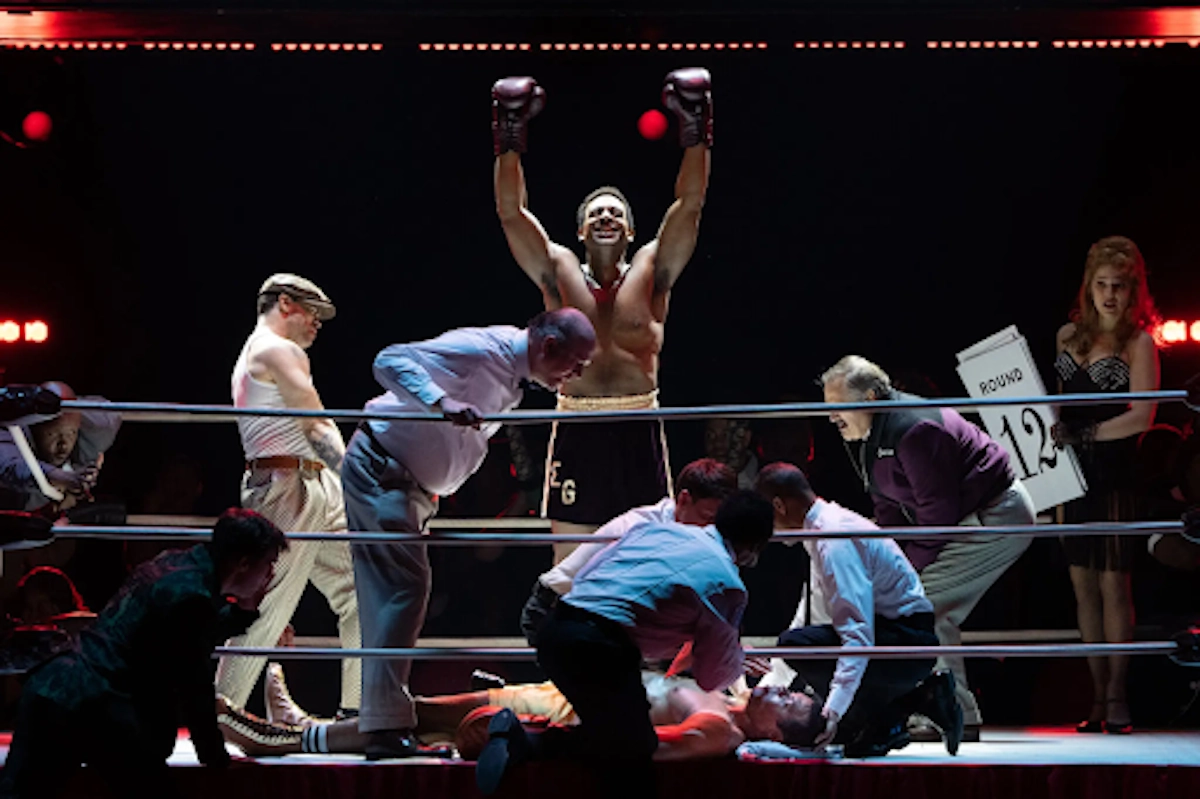

But one thing I’ve never seen onstage is a boxing ring. Until now.

Champion (1 p.m., Saturday, May 20, USCB Center For The Arts) is about welterweight boxer Emile Griffith, an immigrant hatmaker from the Virgin Islands who not only had a tough childhood but is a closeted gay man. Enraged by a homophobic taunt from challenger Benny “The Kid” Paret during their third bout at Madison Square Garden on March 24, 1962, Griffith turned into a human pile-driver, unleashing a torrent of blows that went unchecked by the referee. Paret collapsed in a coma and died 10 days later.

The story is told in a series of flashbacks by an elderly Griffith (sung by Eric Owens), who is suffering from pugilistic dementia. Act I deals with Griffith’s childhood and career, while Act II covers his disastrous marriage and his brutal assault after leaving a gay club. He achieves redemption when he comes to terms with the injured child he once was and asks forgiveness from the family of the man he killed.

Champion is the first operatic work by jazz trumpeter Terrence Blanchard, a five-time Grammy Award winner and composer for Spike Lee’s films. His second opera, Fire Shut Up in My Bones, had a sell-out run at the Met last season.

There are a number of challenges to bringing Champion to the Met stage. First of all, opera singers are not known to be paragons of physical fitness. But bass-baritone Ryan Speedo Green lost 100 pounds and went into training for the role of Griffith, practicing jabs, combos and weaves. “People think that punching is the hard part of boxing,” he told the New Yorker, “but it’s actually the footwork.”

Another challenge was the choreography. How do you make the match look realistic and violent without anyone getting hurt? Griffith and Paret also sing while they’re in the ring and would become too winded if they were actually throwing punches. The Met’s fight director, Chris Dumont, decided that the best way around this was a stylized approach. When a blow lands, the singers freeze as if they are in a snapshot. Other sequences are depicted in slow motion.

In order to portray Griffith’s epic barrage in the deadly knock-out round as realistically as possible, Dumont watched video of the actual fight. “The 17 blows are fairly close to what it was in real time,” he told the New York Times, “We are not actually landing the blows, but moving fast enough so the audience is tricked.” The action then moves to slow motion as Paret is falling to the mat.

It didn’t hurt that Blanchard actually knows something about boxing, having sparred informally with his friend, the actor and former professional boxer, Michael Bentt. To make sure the production had the right look, Blanchard asked Bentt to consult.

“I’m not an expert on opera, but I’m an expert on rhythm,” said Bentt in an interview with the Times, “and boxing is rhythm.”

He pointed out that the boxing mitts, which are used by a trainer to block a fighter’s punches, were too clean.

“Make them look gritty,” he advised. “Rub them on the concrete to get them nasty looking. There’s nothing clean about the world of boxing.”

The orchestra is an active participant in the show, with the snare drummer focused on the boxing punches and synching his snare shots accordingly. Actual bells sound to begin and end the rounds, and conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin even appears in the orchestra pit in a boxer’s robe at the start of the second act. Also look for the carnival scene in St. Thomas to have the same vibrant energy as the stepdance that was such a hit in Fire Shut Up in My Bones.

Ryan Speedo Green, who sang in Fire last year, shares a similar history with Griffith in that he grew up poor in a trailer park in Virginia. Also like Griffith, he was abused as a child, spending time in juvenile detention for threatening to kill his mother. As for his unusual name, his given name is indeed Ryan. But the Speedo?

“My dad was an amateur bodybuilder,” Green told the New Yorker, “and so as a joke on April Fool’s Day — I was born on April 1 — he named me after his favorite underwear.”

Magic happened when Green was 14 and went on a field trip to the Metropolitan Opera, where he saw Carmen. From then on, his life changed. A couple years ago, he found himself onstage at the Met, singing in seven shows at roughly the same time in English, Russian, Italian, and German. One of those roles was the toreador Escamillo in Carmen, the very opera that had inspired him to sing in the first place.

La Tonia Moore from Fire returns to sing Griffith’s neglectful mother, and mezzo-soprano Stephanie Blythe does a great cameo as the “I’ve-seen-it-all-and-then-some” bar owner.

Champion is similar to Fire in that it explores these same sex attractions that caused author Charles Blow such early anxiety. In fact, one of Champion’s most beautiful and moving moments is when Green sings the almost Puccinian aria, “What makes a man a man?”

You may be wondering why Blanchard, who is straight, was drawn to this material.

“The thing that really got me about Emile’s story is the whole idea of accomplishing something major in your life but not being able to share that openly with someone you love,” he said in a Met interview. “Thinking about the inequities that people experience in the world because of social dogma — that really appealed to me as a subject. There’s a moment when Griffith says, ‘I killed a man, and the world forgave me. Yet I loved a man, and the world wants to kill me.’ That, to me, was a very, very, very powerful notion.”

“I grew up in New Orleans, Louisiana, going to Central Congregational Church,” Blanchard continued, “and if you truly believe in a higher power, then you have to believe that we’re not all going to come in the same flavor. We need to celebrate our differences.”

Even more rewarding for Blanchard than seeing his work staged at the Met has been the opportunity for African American singers to showcase their talents in leading roles in big productions. “With Fire, they were all part of something that was successful and that’s going to be with them for the rest of their careers,” he said. “I loved watching them take ownership of the material and the music, making it their own.”

If Champion resonates with audiences, perhaps we can look forward not only to more operas from Blanchard, but more sports operas as well. If opera is about anything it’s about people under extreme pressures with extreme emotions, and professional athletes surely qualify. Perhaps in the future, seeing something like a boxing ring onstage won’t be so unusual after all.

WANT TO GO?

What: Champion

When: 1 p.m., Saturday, May 20

Where: USCB Center for the Arts

Run Length: 2 hours, 50 minutes with an Intermission between Acts I & II.

Tickets: Online at the Center for the Arts website or at the door, $22/$20 for OLLI members.

Content Advisory: Adult themes, sexually explicit language and violence. Sung in