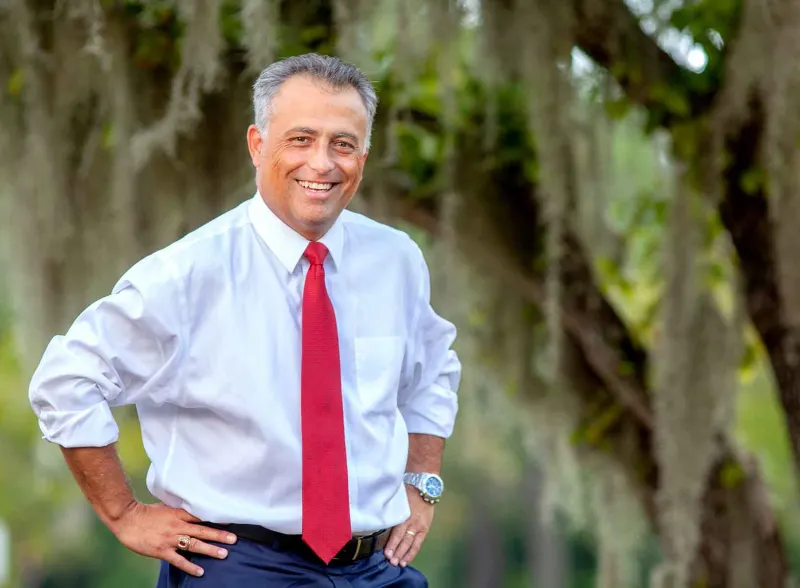

By Donald Wright

Consuming nutrients is necessary for human sustenance, and it is no less ethical eating meat than eating anything else that fits the bill — or fills the tummy.

Beyond health concerns, the major reasons commonly offered for not eating meat are based on prevailing notions of the relative values of living things. Our self-serving understanding of the natural order places animals on a higher plane than plants and humans on a higher plane than other animals. The more similarities a living entity shares with us, the less inclined we are to eat it.

Based on this, some believe it ethical to eat plants but not animals; others believe it ethical to eat animals, but not those with certain human characteristics, often drawing the line at those possessing a central nervous system. Most avoid eating animals considered our near relatives — chimpanzees or orangutans, for instance — and virtually all abstain from eating other humans. Fair enough.

But Linnaeus did not consult plants, or even orangutans, when he developed, and others refined, what came to be widely accepted ideas of these biological hierarchies, and our ideas about the relative value of living things have a record of being badly miscast. After all, a century ago, learned people of European descent held that such persons as themselves, termed “Whites” for their pale skins, were superior to such other human groupings as “Blacks,” “Browns,” “Yellows,” or “Reds.”

Decisions not about whether we should eat these perceived lower orders, but about their mental and physical capacities, their life and death, and how we should treat them, were based on this hierarchical notion. That we now hold such racist ideas in contempt shows how thoroughly some of our most deeply held sentiments can change over a few generations.

Current ideas about biological hierarchies may be as ripe for change as were those about race a century ago. Already, such basic ideas supporting how we deal with animals as the centuries-old belief, handy for carnivores, that certain animals feel neither pain nor fear have been proved incorrect and have thus altered in some measure how we treat and kill the animals we consume. Respected botanists also now theorize that plants also feel pain and even recognize affection.

In considering the biological hierarchy, might we soon cease to place animals in a higher order because, among other negative characteristics, they consume oxygen and give off carbon dioxide, take — sometimes violently — what they need for their nourishment and excrete what remains wherever it strikes them, and kill one another in mating rituals, or to claim dominance, or for a perceived political gain?

At the same time might we not raise to a higher plane the plants that take in CO2 and give off oxygen, create their own food from sunlight, renew the soil they grow in once they die, and in some cases offer up nourishing vegetables, fruits, nuts, and nectar for the consumption of others?

If such ideas gain acceptance, should they form the ethical basis for what we eat? If so, it might then be ethical to eat animals and not plants.

As with all animals, we humans cannot sustain ourselves without consuming something that once was alive. Rather than limit which living things we consume based on current notions of which is more advanced, or suffers more in the process, is it not better to treat with consideration the plants and animals we eat, making sure their lives are decent and their killing carried out as humanely as possible, while giving thanks to the living entities whose lives we take so that we may survive another day?

Donald Wright has been a Beaufort resident since 2014. Retired, he has authored several books.