By Emily Loader

Juneteenth recognizes the agony of subjugation while celebrating growth and the yet-to-come brightness of the future. The summer holiday officially marks the long-time-coming date of black Americans learning of their freedom to shed the shackles and horrors of slavery. And it promotes the sharing of the stories of local heroes who moved from slavery to impact their time and ours.

Every year, women from of the Hilton Head Stake from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in the Lowcountry choose a monthly book to help expand their horizons and foster open dialogue. For the month of May 2023, the group chose Rebecca Dwight Bruff’s historical fiction Trouble the Water.

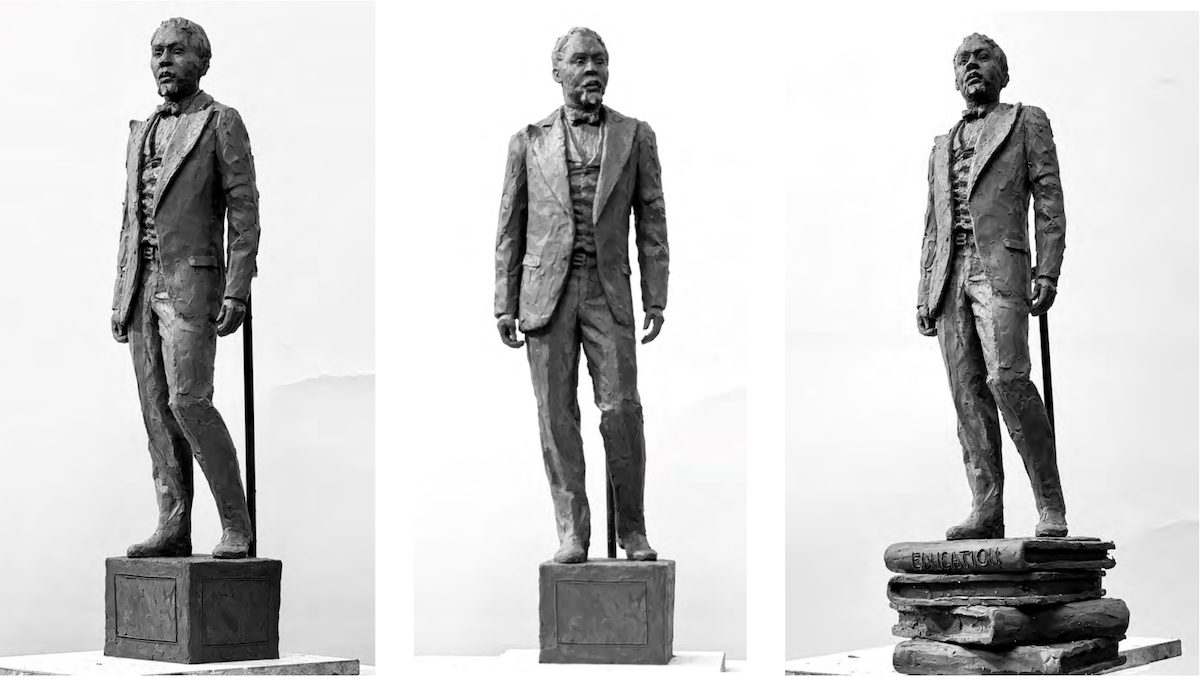

The story captures the history of Beaufort’s former slave Robert Smalls (1839-1915), from commandeering the CSS Planter during the Civil War through gaining his own freedom and then onto his incredible trajectory serving not only his hometown, but also his country.

Smalls served in the state legislature as a delegate in the 1868 and 1895 State Constitutional Conventions, the South Carolina House and Senate, and as a congressman for five terms. He was instrumental in bringing the free education to all children, which occurred first in South Carolina. In 1870, Smalls wrote the legislation that yielded compulsory education in the state, impacting free schooling for the country.

Upon finishing the book discussion, the group of local women decided to explore Beaufort churches, graves, homes, and other landmarks of Robert Smalls and his family in June of 2023. They chose to immerse themselves in the tangible history of this American hero who impacted their own lives, uplifting others as he smashed cultural bans. Much like the author Rebecca Dwight Bruff relocated to Beaufort to research the complicated dynamics of Smalls’ pre- and post-war relationships. His associations were full of accurate twists coupled with fictionalized verbiage to fill historical gaps.

After visiting the graves of Smalls and his family members at Tabernacle Baptist Church on Craven Street, Katie Stanley of Hilton Head Island said, “Being in the same locality as Robert Smalls and his family is a way to honor people you respect and help you to understand them further.” She explained to her children what a “great man” Smalls was as a human and leader of his community.

I sat at the lunch table at Market Café, Beaufort’s former City Hall building, to discuss the experience with these ladies.

Mackenzie Dallon offered, “Actually being at First African Baptist Church, where Robert Smalls was a member, gives the book so much more depth. Pausing at the church’s door where he stood and touching the same columns he did brings the man from the book to life. With my own eyes I’m seeing what he really saw with his own eyes. I came here to understand the place where Smalls and many people in this story experienced their trials.”

Adalie Call added, “There’s something that affects me emotionally when I’m here, feeling where the personal struggles and battles that we have been reading about in the book Trouble the Water actually happened.”

Katie Stanley led the discussion about how a location can speak for itself: offering the rhetoric of being where, for example, Robert Smalls lived as both a slave and later as the home owner.

“When you are at a place like Robert Smalls [childhood and late adult] home, you can allow the location itself to speak: showing what happened then and what has occurred since,” Stanley explained. The participants remarked about how the land around the home has been built upon and pondered the location of Robert Smalls and his mother’s “backhouse,” which was also called the dependency, described like a shed in the book.

In the book Trouble the Water, Robert Smalls enters the tax office and hands $600 to the clerk. With intention, I am adding a long passage here, as it encompasses pivotal viewpoints.

“Good morning, sir. 5–1–1 Prince St.,” I told him.

I remembered him from my childhood; he ran the post office, and had a small printing business as well. The war had closed his business, and to be honest, I was surprised that he was back in town in any capacity. But here he was, working in the tax office, collecting property taxes from those of us who could afford them, and for that price we took full title to the property.

“Name?” he asked, without looking up.

“Smalls,” I said. “Robert Smalls.”

His head popped up, and he fixed me with a scowl. “Smalls! You thief — first, the boat, and now the house, is it? Well, we’ll see how things work out.” He turned to the file box behind him, and taking his time, found the document, bludgeoned it with his ink stamp, and shoved it under the window at me.

“Thank you,” I said.

The tax clerk’s response was not the only or worst, expression of resentment, but neither was it common, and for that I was grateful. I had known the people of Beaufort to be complex in many ways — proud of and entitled by their wealth, and also generous with it; stubborn and insistent on the right to hold slaves, and also, with a few exceptions, judicious to them as well; profoundly damaged in defeat, and also somehow gracious in pain. I knew that some of these people were proud to claim me as a citizen, even as they dealt with the wounds of war.

I walked the short distance from the tax office to Prince Street, heart pounding. This house. My house. Our home now. I walked in, through the front door this time, remembering waiting for permission at the back door only a few years earlier.

Robert Smalls did indeed purchase the home he once was enslaved in. It was sitting on the front porch of that very home where “his extraordinary life came to an end at age seventy-six,” the Beaufort Gazette reported 100 years after the event.

“These slave locations are the sites of such suffering that you feel compelled to pause. We want to honor not only this man and his rise, but share how he impacted the city and citizens today,” Dallon explained, “Looking out at the rivers [from] where he stood helps bring his legacy to life for me personally.”

Emily Michalak Loader enjoys writing and editing for Market4Profit in Charleston and serving as Stake Communication Director in Bluffton. She graduated from Texas Tech University with a PhD in English with an emphasis on Technical Communication. When she’s not looking into the nitty gritty of software and hardware manuals or the information of a press release, she loves spending time with her family on long bike rides.