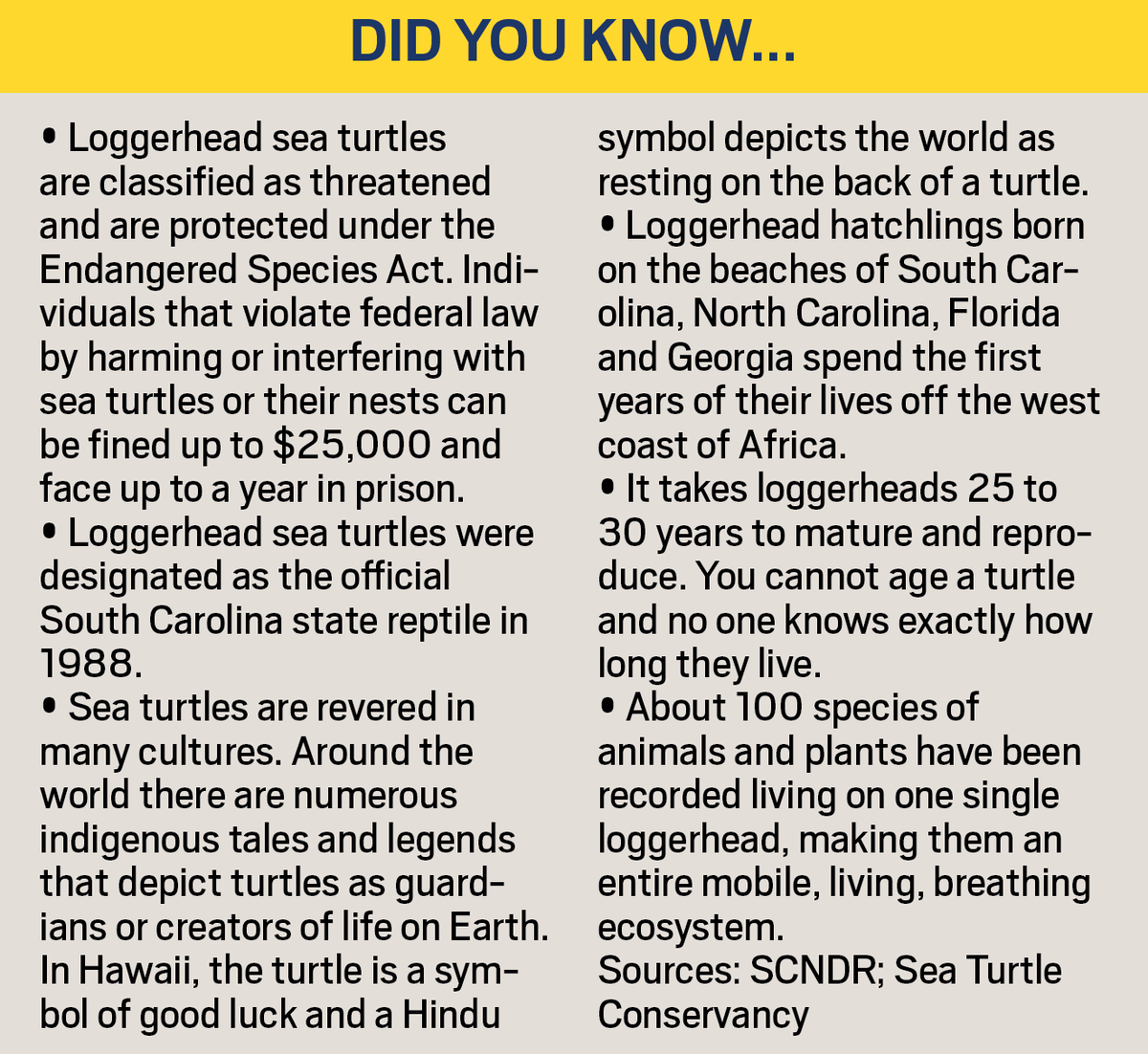

Photo above: A mother sea turtle heads into the ocean after laying her eggs on Fripp Island. Photos provided by Fripp Island Turtle Team.

By Sally Mahan

Tracking loggerhead sea turtles – reptilian behemoths that have been swimming the seas for millions of years – is like being a CSI investigator.

You have to look at the small and large clues on the beach.

Are there large, distinctive tracks that the mother-to-be leaves in the sand with her flippers as she makes her way onto the beach to deposit her eggs into a nest? Are there areas that stand out on the beach due to a large disturbance in the sand? Is there a big crescent shape in the sand?

These are just a few of the things that the volunteers with the Fripp Island Turtle Team have to take into account in order to not only seek the nests out, but also to help protect them.

Why is that so important?

The loggerhead sea turtle is the world’s largest hard-shelled turtle, topping off at an average of 440 pounds (the largest that has been found was 1,202 pounds).

They also contribute in many ways to the coastal and marine ecosystems.

One way is through unhatched nests, which are a good sources of nutrients for the dune vegetation (even the leftover egg shells from hatched eggs provide some nutrients). As a result, dune vegetation is able to grow and become stronger. In turn, stronger vegetation and root systems help to hold the sand in the dunes and protect the beach from erosion.

Most importantly, they are considered an endangered species and are protected by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, according to the Sea Turtle Conservancy.

And many of these amazing creatures lay their eggs in nests on the beaches of South Carolina.

Sea turtle nest numbers broke records across the Southeast in 2016, including in South Carolina, where a total of 6,444 loggerhead nests were laid – the highest number counted since the founding of SCDNR’s sea turtle program in the late 1970s. That’s still a long way from the federal Loggerhead Recovery Plan’s goal of 9,200 nests.

Reaching that goal is difficult for various reasons.

Untended fishing gear is responsible for many loggerhead deaths. Additionally, loss of nesting beaches and the introduction of exotic predators have also taken a toll on loggerhead populations.

Janie Lackman, who has led the Fripp Island Turtle Team for 10 years and holds the SCDNR permit to do so, said that loggerheads also have numerous predators, especially early in their lives. Egg and nestling predators include seagulls, snakes, raccoons, and most particularly on Fripp Island, ghost crabs.

Once the turtles hatch and make their way into the ocean, predators of the loggerhead babies include fish, such as parrotfish and moray eels. Adults are rarely attacked due to their large size, but may be preyed on by large sharks, seals and killer whales. Boats are also a threat. In Sanibel, Fla., five loggerheads were killed in as many days by boaters.

One of the biggest issues is that very few of the hatchlings make it to the ocean, and that is sometimes due to humans.

Lackman said that the mother comes out of the ocean to dig a nest about 18 inches deep with her hind flippers in the dry sand above the high tide line. And while numbers vary, a mother lays about 120 ping-pong sized eggs about four to six times each season, which is from May 1 to Oct. 31 in South Carolina.

Sounds like a lot of turtles. But here’s the rub: Only about one in 1,000 make it into the sea and one in 10,000 reaches maturity. And this year may be more dicey than usual.

“Many of our beaches experienced heavy erosion last fall during Hurricane Matthew, reducing the amount of ideal sea turtle nesting habitat,” said Michelle Pate, SCDNR biologist and sea turtle program coordinator. “As a result of that we may see more nest relocations this season, as trained staff and volunteers move eggs to safer ground, but overall we’re hopeful for another year of high nest numbers.”

That’s why groups like Lackman’s are so imperative to protecting the turtles.

This year on Fripp Island there are 31 sea turtle nests (as of the end of May). As you walk the beach you may notice areas squared off with poles and orange tape warning beach-goers to stay away from the nests. At the direction of the SCDNR, all of the nests on Fripp above the “king high tide line” must be left where they were laid. All other nests are relocated to higher ground further back from the ocean.

Each morning on Fripp Island, volunteers are divided into two groups of about four people each (there are a total of about 20 volunteers who rotate patrol days). One group heads to the south and the other heads north.

“We’re looking for signs of nesting, like large areas of disturbance,” said Lackman. “We look for incoming and outgoing tracks into and out of the ocean. Where did she go? How long was she there? Is there uprooted vegetation? Is there a large crescent in the sand (also a sign of a nest)?”

Then they check on the eggs.

“We use a probe stick to find the chamber, which is about 8-10 inches across and is shaped like an upside-down light bulb. We use it very carefully to find a soft spot, then we use our hands and dig down to confirm whether we will need to relocate the nest if it’s not in a viable location above the tide line.”

If necessary, they move the eggs to a better location by digging a relocation chamber.

“First we dig the new nest, then we have to get them out of the old nest, but we cannot rotate them,” said Lackman. “They have to be lifted straight up and straight down. If you rotate it, it’s scrambling the egg. We then put them into a sand-lined bucket and count them coming out of the old nest and count them again when they are placed in the new nest.”

The incubation period is around 80 days, and predators are constantly looking for them. Then the hard part begins. The eggs hatch and the hatchlings have to dig through the sand to the surface, usually at night to escape predators and when the sand isn’t as hot as it is in the daytime.

This is also when humans most often get in the way.

The hatchlings enter the ocean by navigating toward the brighter horizon created by the reflection of the moon and stars off the water’s surface.

When there are other types of light on the beach at night the hatchlings get confused and will head away toward that light instead of heading toward the ocean.

“The issue we have with lights come from people,” said Lackman. “Lights out – and that includes flashlights and other lights from cell phones – is also very important to mom because they can deter her from coming onto the beach and laying her eggs.”

Helping to keep these creatures alive is rewarding and challenging, but it’s something Lackman loves.

“My parents purchased a home on Fripp about 25 years ago,” she said. “I saw a hatchling and I was hooked.

“They just amaze me. They’re like little tanks. You see these 2-inch hatchlings that are so driven, and everything eats them! Birds, dolphins. They have such a slim chance that I just want to help them and help make sure future generations see them.

“We have two young girls walking with us this year and just seeing their excitement, well, that’s what I love. We try to get kids involved by teaching and educating them. But we need everyone, from the people who live here to the visitors who come here, to support our efforts in keeping these amazing creatures alive.”

The 10th annual Fripp Island Turtle Team’s fundraiser, the 5K Turtle Crawl on Fripp Island, will be held on July 14.

Participants can sign up on the group’s Facebook page.