By Allen Chaney

The tragic death in custody of Easley Jeffcoat, a 16-year-old boy arrested for nonviolent and noncriminal conduct, is but the latest consequence of the South Carolina Department of Juvenile Justice’s chronic failure to protect children in their care.

The truth is, every child in DJJ’s custody is in danger.

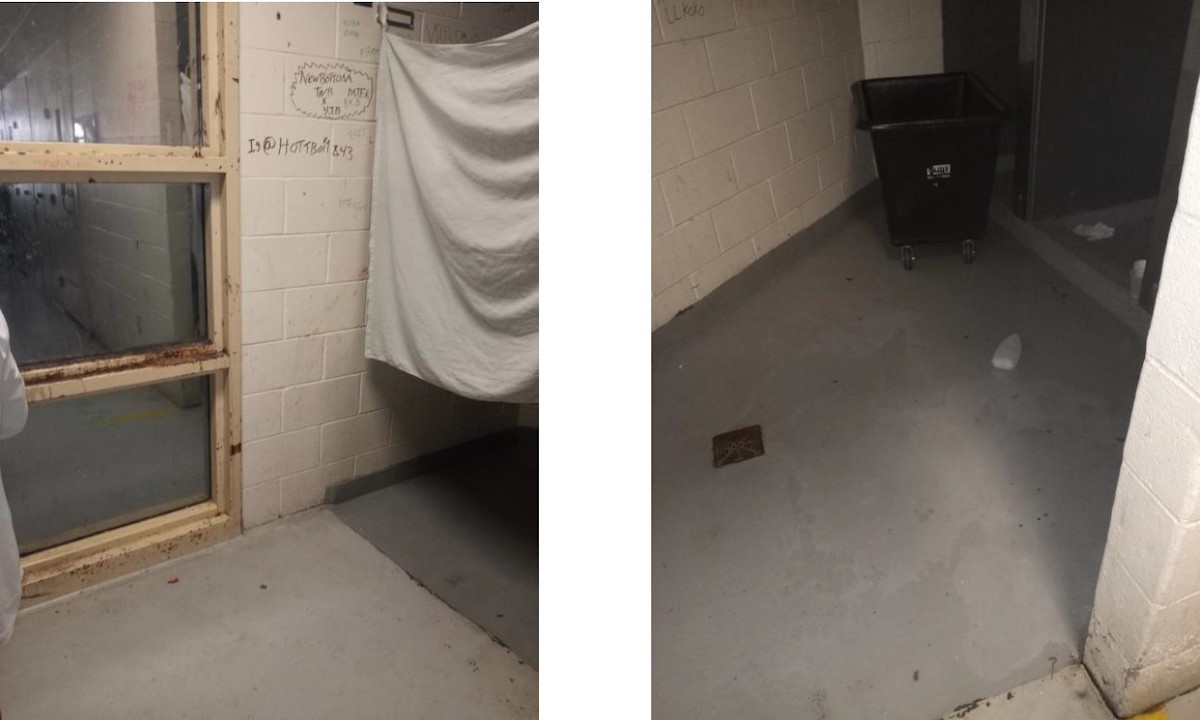

Facilities are staggeringly overcrowded, woefully understaffed, and chronically failing to meet the physical, mental, and emotional needs of vulnerable and traumatized youth. Without radical reform — including a dramatic reduction in incarceration — there will be more casualties.

The public facts are shocking enough, but we at the ACLU of South Carolina have discovered more evidence during our ongoing lawsuit challenging the conditions in these facilities, SC NAACP v. SC DJJ.

Overcrowding

DJJ’s Juvenile Detention Center (JDC) is where most children are held while they wait to resolve their delinquency cases. Located in Columbia, JDC is built to hold 72 children.

But because of over-incarceration (often for status offenses, like truancy), delays in family court proceedings, and the closure of some county-based facilities, JDC regularly detains more than 130 children.

As a result, as many as 85 children are forced to spend each night in “boat beds” (plastic bins the size of sleeping bags) on the floors of unsecured hallways and common areas.

Understaffing

DJJ is chronically understaffed. At JDC, for example, one-third of security positions are unfilled. As a result, 130-plus children are frequently supervised by only six to eight correctional officers.

Other facilities are being operated with less than half the staff necessary to maintain security.

Violence

Years of overcrowding and understaffing have led to tragic consequences.

DJJ’s own violence statistics paint a haunting picture.

In May and June of this year, there were 197 youth-on-youth assaults and 148 violence-related injuries across DJJ’s 5 secure facilities. Children have been hospitalized for head injuries, had their jaws broken, and had teeth knocked out.

Children have been attacked for not joining gangs, for refusing to be extorted, and for no reason at all. Some facilities are so dangerous that staff have refused to come to work out of fear for their own safety.

Misuse of solitary confinement

Overcrowding and understaffing have created an over-reliance on placing youths in isolation.

In violation of federal law, DJJ uses prolonged solitary confinement (for days or weeks at a time) as punishment for misconduct. Officials also use facility-wide isolation (i.e., locking everyone in their cells) to compensate for their inability to ensure children’s safety.

Given the well-researched and long-lasting developmental harms caused by isolation, this “solution” merely replaces physical harm (exposure to violence) with mental and psychological harm.

In fact, research shows that more than half of all suicides attempted in juvenile facilities occurred during periods of isolation.

Lack of mental health services

By DJJ’s own estimation, the majority of children in their care meet criteria for at least one mental health disorder. Despite that, most are never screened, evaluated, diagnosed, or treated.

Rather than receiving care, some children are mistreated because of their impairments.

One child with autism was held in isolation because correctional officers lacked the time or training to accommodate his behavior. Another child suffering from psychotic episodes was held in solitary confinement and was forced to rely on another child to bring him food to eat.

Even in the rare instances where a mental health professional intervenes on behalf of a child, their recommendations — for example, that a child should be removed from isolation — are ignored by security personnel.

What can be done?

First, South Carolina must stop arresting and detaining nonviolent children. Youth who are truant, run away from home, or possess alcohol need intervention — not arrest and incarceration.

Second, we need a speedy trial law that requires solicitors and family court judges to resolve delinquency proceedings more quickly, so that youths are not stuck in pre-trial detention.

Third, DJJ needs more funding so that they can provide basic physical safety and meaningful access to the rehabilitative care demanded by South Carolina law.

South Carolina’s treatment of detained youth doesn’t just harm the children; it also exacts a grave social cost.

Children held by DJJ will be released back into society. At present, they are released far worse off than when they arrived — and our state is worse off as a result.

Public safety demands a better system where children stand a real chance at rehabilitation.

Chaney joined the ACLU of South Carolina as legal director in July 2021. He brings a deep ideological commitment to civil liberties and a passion for protecting and vindicating the rights of the poorest and most marginalized members of our society.