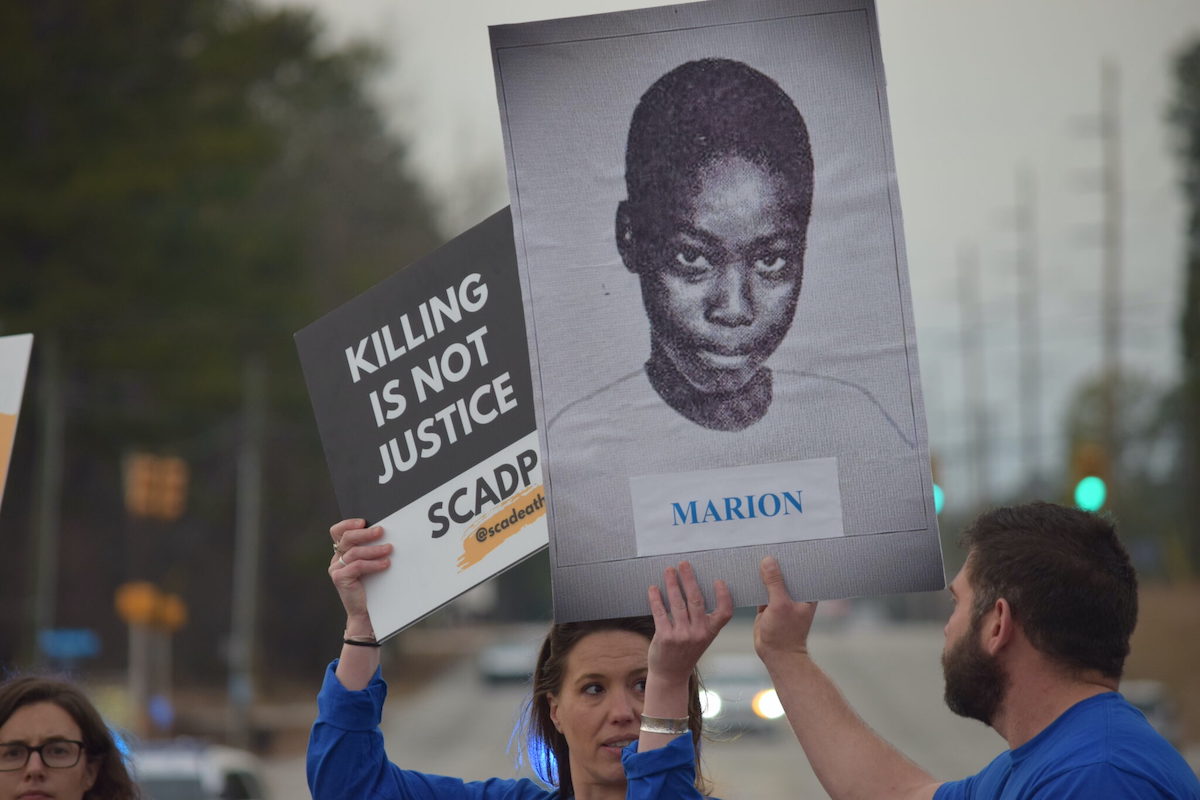

Marion Bowman was 3rd death row inmate executed in SC since September

By Skylar Laird

SCDailyGazette.com

COLUMBIA — Marion Bowman died Friday night by lethal injection in the country’s first execution this year.

His recorded time of death was 6:27 p.m.

The roughly 30 protesters outside the prison gates sang “Amazing Grace,” Bowman’s favorite hymn, after receiving confirmation of his fate.

His final minutes

The curtain in the death chamber opened precisely at 6 p.m.

Bowman, wearing a green jumpsuit and strapped to a gurney, turned his head toward his attorney, Boyd Young, and nodded.

Young read Bowman’s last words, a lengthy statement that concluded with one of his poems. Bowman maintained his innocence up to the end.

“I did not kill Kandee Martin,” began the statement. “I’m innocent of the crimes I’m here to die for.”

Bowman acknowledged the pain Martin’s family felt in losing her, as well as the love of his friends and family and the companionship he found during his nearly 23 years on death row.

He stared up at the ceiling, eyes closed, as Young read. “We are not what the state labels us to be,” the statement concluded. “We are kind, caring, loving people, and it’s a shame the world can’t see that.”

Members of Martin’s family, who are legally allowed to attend, were absent from the witness room.

Young and an attorney from the solicitor’s office watched from the front row, both occasionally wiping at their eyes.

Behind them sat media witnesses, including a reporter from the S.C. Daily Gazette.

At the end of the three-minute statement, as Young took his seat again, Bowman looked toward him again and mouthed something indecipherable to media witnesses through the glass partition. Young replied, “Thank you.”

The execution began at 6:04 p.m. Bowman, still staring at the ceiling, took several deep, loud breaths, puffing out his lips and cheeks with each one. Those subsided into shallower, quieter breaths.

Bowman’s chest stopped moving at 6:06 p.m. At 6:26 p.m., a doctor entered the room and placed a stethoscope on his chest and a hand on his neck. A voice on the intercom one minute later announced that the execution had been carried out.

The length of time was similar to previous executions. Bowman showed no outward signs of pain.

For his last meal, Bowman ate fried seafood, including shrimp, fish and oysters; chicken wings and tenders; onion rings; banana pudding; German chocolate cake; cranberry juice; and pineapple juice.

Bowman chose to eat the meal Wednesday, consuming normal prison food for his final days.

In the hour leading up to the execution, people who gathered outside the prison gate to protest the death penalty included Deidre Kelly, of Rock Hill; Mary Rider, of Garner, N.C.; and Wilna Petion, of Boyton Beach, Fla. The three spoke about Bowman’s case and how he maintained his innocence.

“Death is final and I just don’t think there’s enough certainty in the justice system,” Kelly said.

Bowman decided not to ask Gov. Henry McMaster for mercy, his attorneys said Thursday. He made the decision after the U.S. Supreme Court declined to intervene, and a federal appeals court denied his request to know more information about the drugs that ultimately killed him. McMaster released a statement anyway saying he’d reviewed the records and would not grant clemency.

Bowman was the third inmate executed after the state resumed the process in September. An unintended 13-year hiatus, caused in part by the state’s inability to get the drugs used in lethal injections, ended after the state Supreme Court ruled that electrocution and firing squad were constitutional methods of execution.

All three inmates chose to die by lethal injection after a 2023 law keeping everything about the drugs secret allowed officials to restock. Inmates, including Bowman, have asked federal courts to require officials release more about the drugs that will kill them, to no avail.

Three more inmates have exhausted their appeals and are eligible to receive death warrants in the coming months. The soonest the next inmate could receive a warrant will be Feb. 7.

The crime

Bowman, then 20, was out with his sister Feb. 16, 2001, when he noticed 21-year-old Kandee Martin standing outside a house with a group of people.

Bowman knew Martin. According to his own statement, the married Bowman and single mother Martin had been having an affair. Attorneys have said Martin had a history of exchanging sex for crack cocaine, which Bowman sold.

Asking his sister to stop the car, Bowman told Martin, “I want my money today,” his sister later testified. If she didn’t give it to him, he said she would be “dead by dark,” his sister and cousin later told a jury.

Later that day, Bowman’s cousin, James Taiwan Gadson, was drinking at a friend’s house when Martin drove up, with Bowman in the car. Bowman told Gadson to get in, which Gadson did, he later testified.

Bowman told Martin to drive to a remote part of Dorchester County. Parked along the side of an empty road, the three got out of the car. Bowman told his cousin he believed Martin was wearing a wire and he was going to kill her, Gadson later testified.

A car passed. The three of them hid in nearby bushes. Then, as Martin started back toward the car, Gadson heard three gunshots. Martin said, “Don’t shoot me no more, I have a child to take care of,” Gadson testified. Bowman shot her twice more, according to trial transcripts.

Bowman dragged Martin’s body out into the nearby woods, and the two took her car back into town. Bowman drove the car around through the evening, at one point trying unsuccessfully to sell it outside of a bar, according to court documents.

Around 3 a.m., Bowman called on a friend, Travis Felder, for help. Travis followed Bowman in his own car back out to that rural road in his own car, where Bowman retrieved Martin’s body from the woods, put her in the trunk of her own car and lit the car on fire, Felder testified.

“You didn’t think I’d do it,” Bowman said to Felder, the friend later recalled.

“Did what?” Felder responded.

“I killed Kandee Martin,” Felder told the court Bowman said.

Firefighters arrived later that morning to put out the blaze and discovered Martin’s body in the trunk.

A jury convicted Bowman in 2002 and recommended the death penalty. Bowman’s family, along with the friends and cousin involved, testified against him.

Bowman disputes the way prosecutors laid out the evening. He didn’t testify during his original trial, but in a December statement released by his attorneys, he gave his own sequence of events.

Gadson was the one to kill Martin, Bowman claimed. Bowman went home after spending the day with his sister and learned about the crime later, when Gadson pleaded with him to go out to a bar, his statement continued.

Bowman declined plea deals that would have allowed him to instead spend the rest of his life in prison because that would require him to admit guilt, he wrote.

“I am so sorry for Kandee and her family, but I did not do it,” Bowman wrote in December. “Her family has suffered a loss that can not be undone. They have been through trials, and appeals, but they have never heard the truth from me. I know this won’t bring them satisfaction, but this is my truth.”

Final appeals

In the months before Bowman’s execution, his attorneys asked the state Supreme Court to overturn his sentence, arguing that prosecutors withheld evidence and his own attorney was racist.

Felder and Gadson testified after receiving plea deals, which could have cast doubt on their stories if jurors knew they had something to gain, attorneys argued. Much of the prosecution was based on that testimony, since no DNA tied Bowman to the scene, the appeal continued.

Also excluded was a statement a fellow inmate made claiming Gadson had confessed to the killing after his arrest, the filing argued.

Knowing about the plea deals and the statement, which the inmate later rescinded, would likely not have been enough to change jurors’ minds, the state Supreme Court decided. Bowman’s attorneys raised similar arguments at different stages of his appeals process, to no avail.

The court also rejected the idea that Bowman’s defense attorney, who is white, was racist against him because he was Black. As did the U.S. Supreme Court, in an order issued Thursday.

Bowman’s current attorneys claimed that his attorney implied there was no reason Bowman and Martin would have been together that night except for Bowman to harm her. He tried to persuade Bowman to accept a plea deal because he had little hope of success as a Black man who killed a white woman, the complaint alleged.

Those quotes were taken out of context, and Bowman’s attorney was not wrong for wanting to warn him about possible racism, attorneys for the state replied. Both courts agreed.

Bowman maintained his innocence in declining to ask Gov. Henry McMaster for clemency. It was unlikely McMaster, a former attorney general, would grant Bowman life in prison without parole. No modern governor has done so, and McMaster denied clemency to the past two inmates who asked.

Not attempting is an unusual decision that was difficult for Bowman to make, his attorneys said in a statement Thursday.

“After more than two decades of battling a broken system that has failed him at every turn, Marion’s decision is a powerful refusal to legitimize an unjust process that has already stolen so much of his life,” the statement read.

Kandee Martin

Martin, 21, got a new job not long before she died. She was learning how to sell mobile homes in Orangeburg, which she was enjoying, said her mother, DiDi Martin, during Bowman’s 2001 sentencing hearing.

She was in the midst of planning a birthday party for her son, Tyler, who would turn 2 years old less than a week after her death. Kandee Martin was going to get him a cake featuring the Sesame Street character Elmo and throw him a party. She and her mom were in the process of sending out invitations, her mother testified.

When Kandee Martin died, Tyler would often cry and ask when his mom was coming home, DiDi Martin testified.

“He loved his mother with all his heart,” DiDi Martin testified. “They had a relationship that you just can’t explain because it was so wonderful.”

Kandee Martin, the younger of two siblings, was a caring person, family members recalled. Several years before her death, she and her mother set up a glamour photo shoot, where they got dressed up and took pictures, her mother recalled.

“I would say she was a loving type young lady, and she cared for everybody and (there was) nothing she wouldn’t do for anybody,” her father, Wayne Martin, said during the hearing.

At the funeral 10 days after Martin’s death, the family kept the casket closed, he added.

“That was the worst thing, not being able to say goodbye,” Wayne Martin said.

Marion Bowman Jr.

Born to a teenage mother and an abusive father, Bowman’s early life was difficult, a psychologist recounted during his sentencing hearing.

When Bowman was a teenager, his mother suffered a back injury that left her bed bound. The responsibility for chores and earning money fell to Bowman and his two sisters, according to court documents.

By the age of 14, Bowman was drinking heavily and selling drugs. He dropped out of school after finishing the ninth grade and suffered a series of tragedies, including the deaths of two beloved cousins and the separation of his mother and stepfather, the psychologist said.

Still, Bowman was a kindhearted person who loved his family and went out of his way to help his aunt, relatives testified during his sentencing hearing.

During his years in prison, Bowman, who’s 6-foot-4 and nearly 400 pounds, has earned a reputation as a “gentle giant,” something his aunt repeated in a statement released by attorneys earlier this week.

“Marion is someone who would do anything for someone else if he is able,” Lorraine Johnson said in the statement.

Bowman always makes a point to ask Johnson how she is and what’s happening in her life. He remains close to his daughter, Marissa, who was born while he was awaiting trial. She had her first child in August, making Bowman a grandfather, according to the state’s statement.

“It has torn our family apart to have Marion be on death row,” Johnson said in her statement. “I do not think that Marion’s mother would recover if he were to be executed.”

His mother, Dorothy Bowman, said as much during his sentencing hearing.

“I don’t want to see my son die, because that’s the only son I have, and I don’t know what went wrong,” Dorothy Bowman said at the time.

Since 2009, as far back as sanctions listed online go, Bowman has received only one disciplinary action in prison, for destroying property in 2016.

Because of his good behavior, Bowman received a job coveted on death row since it meant more time out of his cell cleaning and collecting meal trays, former associate Warden Ralph Hunter said in a statement filed with the state Supreme Court.

“Even though Marion was a big man, no one was concerned about him causing trouble,” Hunter said.

Bowman is also a prolific poet. Leading up to his execution, his attorneys released a 58-page collection of his poems, titled “My Thoughts.”

“Some were used as words of encouragement, some as a way of venting, and others were about what was going on around me,” Bowman wrote in a brief introduction.

Some end with Bible verses, a reflection of the Christian faith Bowman found while in prison. One that repeats reads, “I was in prison, and you visited me,” from Matthew 25:36.

Bowman’s final statement

Read by his attorney Boyd Young:

“I did not kill Kandee Martin. I’m innocent of the crimes I’m here to die for.

“Living behind these walls has taught me a lot about loss and grief. It is never easy, but I have learned to find comfort in sharing good memories and funny stories. My suffering will soon be at an end, but I know it is the beginning for others. Please keep your head up, remember I love you, and please share your memories of me.

“I know that Kandee’s family is in pain. They are justifiably angry. If my death brings them some relief and ability to focus on the good times and funny stories, then I guess it will have served a purpose. I hope they find peace.

“To my family, friends, and supporters, I have nothing to give, but I have gained so much. I have tried to give a good return on your investment with love and care.

“I had bad moments but never a bad day because there were so many people that I could reach out to, investing in me and giving me a hand up. We all ended up as family, and I got a whole lot of family. Thank you.

“Over the years I have learned that we are labeled as the worst of the worst. None of these guys that I have gotten to know and grown to love are the people that they were when they had their moment that cost them everything.

“If the world could see us in our day to day, they would have a different view of the death penalty. We all pray for grace and forgiveness, but the outside world is stuck with images of monsters perpetrated by the state, while our real voices are silenced.

“We are not what the state labels us to be. We are kind, caring, loving people, and it’s a shame the world can’t see that.”

Skylar Laird covers the South Carolina Legislature and criminal justice issues. Originally from Missouri, she previously worked for The Post and Courier’s Columbia bureau. S.C. Daily Gazette is part of States Newsroom, the nation’s largest state-focused nonprofit news organization.