Bill would limit legislators to 4-year terms, give governor 4 appointments on a larger screening panel

By Jessica Holdman

SCDailyGazette.com

COLUMBIA — A Senate compromise on changing how the Legislature picks judges newly gives the governor some input in the process but retains legislative control.

The unanimous vote Thursday in the Senate followed days of behind-the-scenes negotiations on an issue that threatened to derail this year’s judicial elections entirely.

Critics, including the attorney general and solicitors of both parties, have complained for months that the current system gives the Legislature too much power over judges, particularly lawyer-legislators who appear before the judges they put on the bench.

Sen. Wes Climer, who pledged last fall to block elections until changes are made, called the bill “a compromise that nobody loves but that everybody can live with.”

“I think it goes a very long way in reducing what heretofore has been undue, outsized influence of legislative politics on judicial outcomes,” said the Rock Hill Republican, who was part of the negotiating team.

Others who worked up the agreement included the chamber’s GOP and Democratic caucus leaders, both of whom are lawyers, and former solicitors in the Senate.

What would change?

It’s not anything close to the comprehensive changes some advocates wanted. Instead, it tweaks the existing process in a way that allows more lawyer-legislators on the panel but with new rules designed to ensure judges aren’t screened by the same legislators term after term.

Those who would prefer to keep the system as is called the changes workable.

South Carolina is among two states where the Legislature elects most judges to the bench. The process involves the Judicial Merit Selection Commission screening applicants and forwarding up to three candidates deemed qualified to the entire Legislature for a vote. Of the panel’s 10 members, six are legislators who are also lawyers. The other four are lawyers appointed by legislators.

The compromise would add two people to the panel, making it 12. Eight of them could be legislators.

The governor would, for the first time, get appointments. He would appoint four, giving the executive branch a third of the say in who advances to a joint assembly vote. One must be a criminal lawyer, one a civil lawyer, one a family court lawyer and one a retired judge.

The House and Senate would each get four appointments: Four made by the House speaker, two by the Senate president and two by the Senate Judiciary Committee chairman.

Sen. Ronnie Saab, who was also part of negotiations, said he thinks the public is more concerned with who actually ends up on the bench instead of who’s on the screening panel.

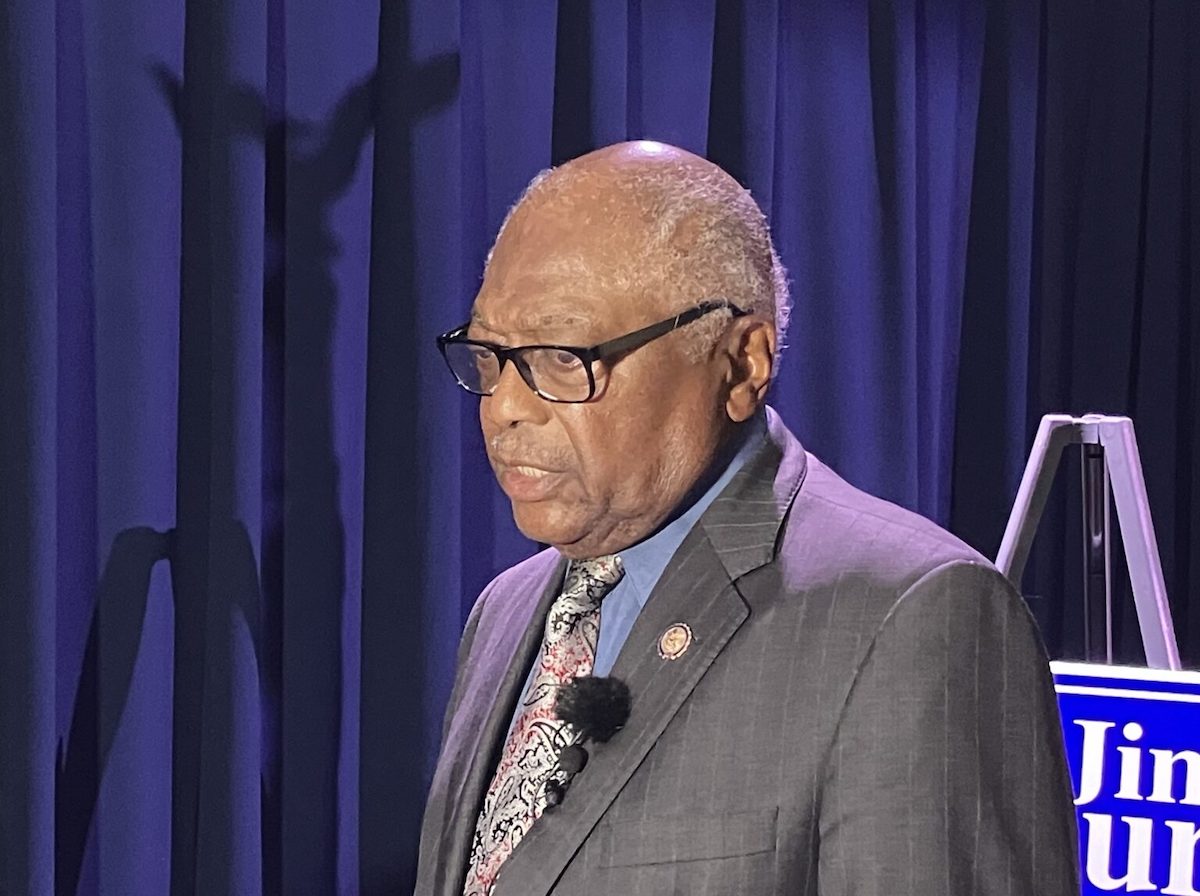

Saab, a member of Judicial Merit Selection Commission since 2017, pointed to a lack of racial and gender diversity. South Carolina’s Supreme Court is the only state high court in the nation without a single female. It currently has one Black justice — Chief Justice Don Beatty — but he retires this summer. The Legislature is set to elect a new justice in June.

“When there is an absence of diversity on a judiciary, I believe that issue in and of itself could erode public confidence,” said the Williamsburg County Democrat.

The agreement ensures judicial elections that were initially scheduled for last month will proceed April 17.

It does not bar legislators who are lawyers from serving on the panel, as many reformers wanted.

But it does term-limit them. Legislators can stay on for four years but then must be off the panel for four years before going back on, which should mean judges won’t be screened for election and re-election by the same legislators.

Climer said that will prevent legislators on the screening panel from entrenching themselves in the process and having “undue influence on the judges before whom they try cases.”

“Any time a citizen of this state enters a courtroom, the only thing that should have a bearing on the outcome of that process is the law and the facts,” said Climer, who is not a lawyer. “The judge’s politics, judge’s re-election, the attorneys’ politics shouldn’t matter. The Legislature’s politics shouldn’t matter.”

The bill also creates a process for removing legislative appointees for misconduct or neglect. And it requires a commissioner to resign if they have an immediate family member or in-law seeking a judgeship.

When the screening panel finds a candidate “unqualified,” it must include the reasoning in its report.

And, rather than being limited to three candidates, the panel could forward as many as six to the Legislature for a vote. The bill requires all of the screenings to be livestreamed for the public.

Finally, the compromise adds more weight to votes cast by senators.

A candidate would need a majority of votes from both House members and senators rather than a simple majority of the full Legislature.

That’s likely to meet resistance in the House. Their greater numbers mean the House decides judicial elections. There are 124 House members and 46 senators. In contested races, it’s the count in the House that really matters.

Another vote Tuesday will officially send the compromise over to the House, where its fate is dubious.

A House committee that’s been meeting since last fall continues to work on its version of a bill changing the judicial selection process.

Just eight weeks remain in the regular session.

Jessica Holdman writes about the economy, workforce and higher education. Before joining the S.C. Daily Gazette, she was a business reporter for The Post and Courier.