A funeral procession on St. Helena Island stopped traffic on a recent Thursday morning and we were all the more blessed for it

By Mindy Lucas

If the turnout for Lucinda Simmons’ funeral service held on St. Helena Island on Thursday, May 20, was any indication of the love and respect the community had for “Mother Simmons,” as she was called, then Simmons was loved and respected an awful lot.

As cars and trucks began pulling off Sea Island Parkway and lining the road just before noon on Thursday, those driving by or slowing down to allow for traffic may have been struck by the sheer number of people in attendance.

Hundreds of friends, family members and neighbors, many dressed in white, poured in for the outdoor service held at Simmons’ modest home just off Mattis Drive.

But what was even more striking was another sight that began to unfold in front of all us “stuck in traffic” that morning.

From beneath a canopy of tall pines just off the side of the road came two majestic white horses, wearing black sashes. With traffic stopped in both directions, the magnificent looking animals took a few tentative steps forward then entered the roadway.

Farther down the line as cars and trucks began stacking up, drivers began to slow on approach as if recognizing the solemn moment for what it was and wanting to soften the noise of their engines as best as they could.

Radios were turned off, windows were lowered and some drivers even seemed to bow their heads.

As the horses clip-clopped their way across the highway, the all-white, glass-enclosed carriage carrying a white casket followed behind them. Behind it walked the pallbearers.

The glass of the hearse gleamed and sparkled in the morning sun, and the scene, framed by live oaks laden with Spanish Moss, was otherworldly. It was also haunting and beautiful and sad all at once.

Watching the scene unfold from behind the wheel of my car, I was not only awestruck, I wanted to know who this solemn procession was for and who this person had been. Because as you’ve probably guessed by now, up until Thursday, I didn’t know the first thing about Lucinda Simmons.

An exception to the rule

Journalists are trained to be objective in their work, but that doesn’t mean we are without emotion. Sitting in traffic that morning, I had a lump in my throat. How could you not?

We are also trained never to insert ourselves into a story, something that’s become rarer these days as social media – with its heightened state of emotion and self-aggrandizing nature – has become the norm, rather than an exception to the rule.

But for this story, call it a column if you will, I’m making an exception, because it’s just as important to know how the story came about as it is to know who it’s about. And because I have a hunch, or call it a strong feeling, Ms. Simmons had something to do with that as well.

So like many who may have sat in traffic there on the highway Thursday morning, wondering who she was or what was happening, I decided to find out what I could and maybe tell her story.

A wife, a mother, a friend and neighbor

If you’re looking for a love story, you’ve come to the right place.

Born in 1925, to Frank and Lucy Johnson, Lucinda Johnson was the youngest of four children.

As a teenager, Lucinda’s first job was in the laundry department on Parris Island. It was there that she met Charlie Simmons, a carpenter and later a veteran having served in the United States Army.

It was love at first sight, at least for him anyway, Simmons’ daughter Valerie Langhorn said by phone recently. As the story goes, he had to work a little for her love and attention.

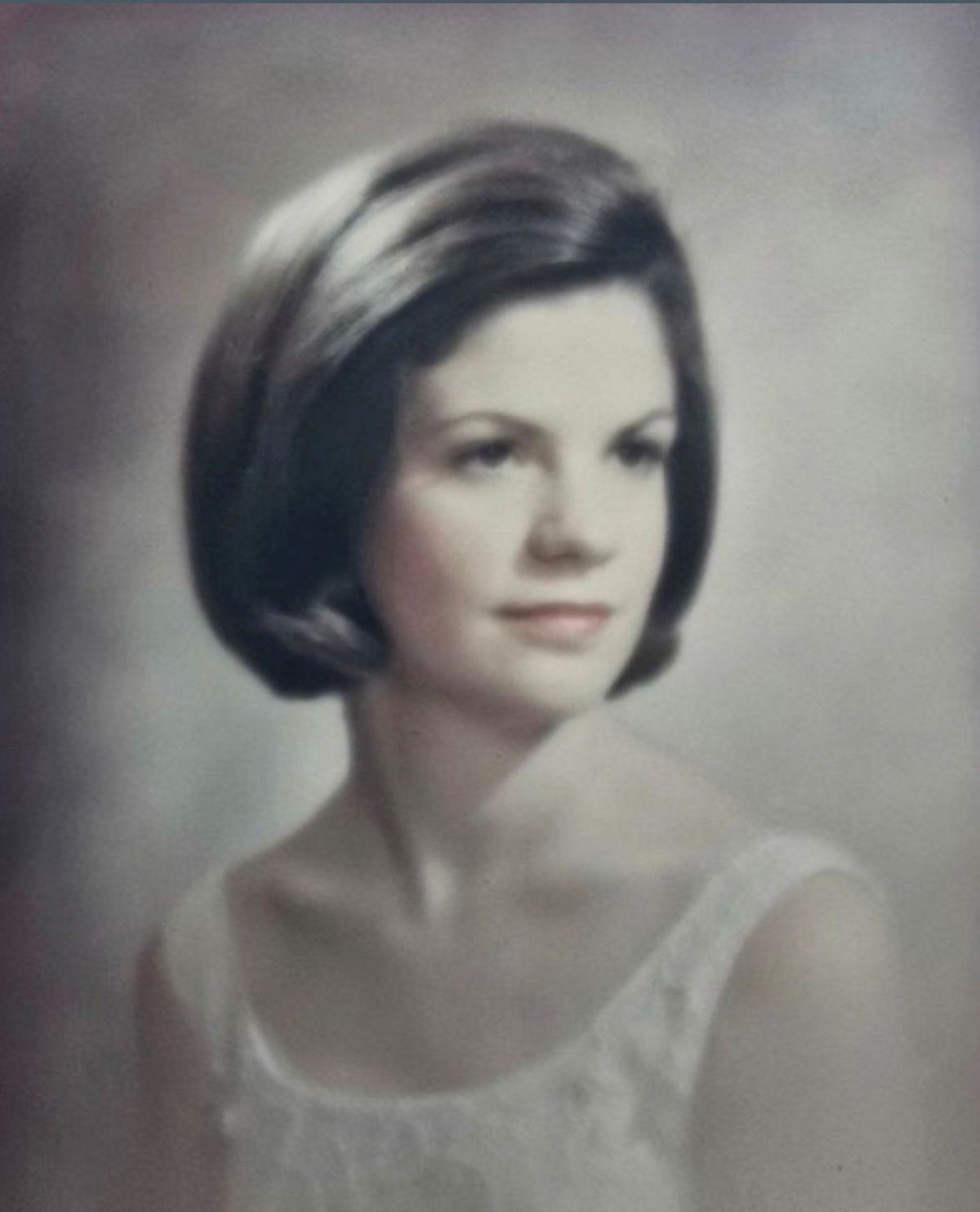

“He had to work for some days or weeks,” she said, laughing. “I don’t know if it went into months, but it was for awhile. I mean look at her at that age.”

Lucinda Johnson was a knockout. Fortunately, Charlie Simmons didn’t have to wait forever.

The two were married in 1943, their union producing four boys, Charlie Jr., David, Daniel and Raymond, and three girls, Lucy, Valerie and Gwendolyn. There was also Marjorie, Charlie’s oldest child, and Bryan, a grandson, they raised as their own.

If you’re looking for a story about love and devotion to one’s family, Lucinda Simmons had that too.

“Mother Simmons” or “Mother Lu” as she was known to her friends, cherished her extended family. In fact, 17 grandchildren, 26 great grandchildren and 11 great great grandchildren called her either Grandma, Grandma Simmons or Granny Grand, not to mention the many nieces and nephews too.

For five generations, she was always there, keeping tabs with lives of her growing family either by phone or in person, and when she died they came quickly and without hesitation from all over – New York, Boston, Virginia, Florida, Georgia, Pennsylvania and of course South Carolina.

If you’re looking for a story about faith and service, you needn’t look any further.

Simmons was devoted to her church, Oaks True Holiness, where she sat on various boards and faithfully attended Sunday prayer, Sunday school and service, Wednesday noonday prayer, Bible study and Friday night services, not to mention revivals and special services.

But Simmons didn’t give lip service to her faith. She lived it.

After working at Garland Knitting Mills in the early ‘70s, then later as a private caretaker caring for people, she went on to volunteer at Beaufort Memorial Hospital for 10 years.

“While dad taught us the importance of hard work and maintaining integrity in all we do, mom taught us the importance of education, honesty, maintaining good character, love for others and acknowledging God in all our ways,” Langhorn wrote in the funeral program.

There are so many more stories and things that could be shared about the life and times of Lucinda Simmons.

Like the fact that she loved hats and was an impeccable dresser.

Or that she had a great sense of humor and loved to read – particularly poetry.

Or that she loved to feed and host people.

But most important of all, Simmons lived her life with grace and meaning, taking time to … well, just be, whether that meant as a wife, a mother, a friend or a neighbor.

“That’s my other mother,” said family friend Theresa Pringle, who dropped by Simmons’ house a few days after the funeral.

As we sat on the screened-in porch of the house that Charlie Simmons built, Pringle and another family friend, Charmaine Treloar, and Simmons’ oldest daughter, Lucy Simmons, took turns sharing stories about “Mother Simmons.”

They recounted how funny she could be, how she enjoyed driving to see friends well into her 90s, and how she enjoyed visiting with the Franciscan sisters just down the road at the St. Francis Center and Thrift Shop.

“She was just a nice lady,” both Pringle and Treloar said.

Lucinda Simmons died at home on a Thursday evening, just after her loved ones said their final words. She was 95.

Sending her to heaven

As the horses entered the yard of the Simmons’ home, a long line of mourners or those paying their respects fell in behind the carriage. They circled the house and came to a stop where her casket was unloaded for the noon service.

It was a beautiful service, I am told, filled with scripture readings, kind words spoken by friends, a eulogy by Columbia pastor and Senator Darrell Jackson and singing by American Idol’s Season 12 winner Candice Glover, who flew in just for the service.

I am told this is what happened because I didn’t stay for the service attended by more than 300 people. I felt it would be intruding on a private family affair, though as one mourner assured me as I stood close to the road, Simmons would have invited me in.

“This is a very public event,” she said.

Instead, I watched from the edge of the property as the service got started then excused myself.

Across the road, I made small talk with Bridger Medlin, the coachman, who was packing up to go home. The carriage was actually a hearse, he explained. A caisson is open while a hearse, such as the one that carried Ms. Simmons, is closed.

Based in Charlotte, N.C., Medlin’s company does probably five or six horse-drawn events a week, but he prefers funerals to weddings, he said, a response that surprised me.

He said he’d rather do a funeral because people are usually appreciative of life in a different way than they sometimes are at weddings.

“I would rather do that than work with some brides who are more worried if the potato salad turned out alright,” he said, with the smile of someone who learned a long time ago not to sweat the small stuff.

“(At funerals) you see people for who they really are then,” he said. “And the family’s hearts are open.”

The horse-drawn hearse was the children’s idea as was the wearing of white, I found out a few days later as I sat talking with Lucy Simmons at her late parent’s house.

“We made sure she was sent to heaven in the way she wanted to be sent,” she said.

Daughter Valerie Langhorn laughed and called her The Queen.

“She wasn’t just the matriarch of the family,” she said. “She was the Queen. I can guarantee you that.”

Her final act

It can be easy to forget.

There are bills to pay, children to raise and jobs to go to. The noise of our everyday lives is so great some days, we forget we’re the ones who turned up the volume.

So sometimes we forget to live our lives. Until a horse-drawn hearse literally crosses our path.

Driving home I tried to remember how the Emily Dickinson poem went. “Because I could not stop for Death, He kindly stopped for me” was as far as I got.

When I got home I looked up the rest.

The Carriage held but just Ourselves –

And Immortality.

It’s become fashionable for people to say they’re trying to “be more present” or “live in the moment” which I guess means they are looking at moments spent with their family, or things that mean something to them, with greater awareness.

All good things, but it’s hard to strike a balance between making the most of each day and doing what you need to do to get by. In fact, I’d say it’s damn near impossible, if not impractical, to “live each day as if it were your last.”

After all we still have responsibilities to fulfill, work to do and miles to go before we sleep. Whether we feel enriched or not, fulfilled or not, for better or for worse our lives go on in all their imperfect glory.

And yet, there are times when something comes along to remind us of something bigger than ourselves. Like the fact that life can be so short. Even the very old will tell you that’s how it is. That it seems to pass in the blink of an eye.

As I sat behind the wheel of my car that morning, watching Ms. Simmons’ hearse cross the road, I wondered if our lives passed by or “transitioning to heaven” as it is called in our part of the world, is as easy as all that. Like crossing a road. One day you’re standing on one side among the living, the next you’re crossing over, so to speak.

Whatever the case may be, I know this: Lucinda Simmons stopped traffic that day.

All those drivers going about their business, heading to work or out to the beach maybe. Wherever and whatever they were going to, their lives came to a halt, if only for a few minutes, for Ms. Simmons’ departure.

Call it her final act of service, but it was a reminder. Whether it was to remember to live your life, and truly live it if you can, or that it can be over in the blink of an eye, it was a reminder.

And what I didn’t know then that I know now, was that we weren’t just watching the life of a dearly departed loved one on her way to her final resting place, we were watching a life unfolding as she crossed.

A life of love and devotion, of work and faith, of boredom undoubtedly punctuated with moments of great joy and yes, sorrow and loss. A life of children being born and generations yet to come, but a long and beautiful life nonetheless.

In the crossing of a road, where loved ones waited on the other side, all this and more was passing us by.

Mindy Lucas, previously a reporter/ writer for The Island News and Lowcountry Weekly, has taken a new position with the Technical College of the Lowcountry but will continue writing for Lowcountry Weekly on occasion.