Nurses at Beaufort Memorial Hospital talk about being on the frontlines of COVID-19

By Mindy Lucas

ER nurse Lauren Singer remembers the first time she saw a coronavirus patient at Beaufort Memorial Hospital.

It was early March and, as Singer recalled by phone recently, the first cases had already hit the United States.

“That’s when things really started happening behind the scenes,” she said, as she remembers when the hospital began ramping up its emergency planning.

Members of the hospital’s emergency management team were meeting two to three times a day. Staff were taking stock of ventilators and PPE, or personal protection equipment. Visitors had been limited to one per patient, but that would soon change as hospitals everywhere would eventually go on lockdown, barring any visitors for patients.

Then one day, there she was. Singer’s first COVID-19 patient.

She may not have been the first for the hospital, but she was certainly Singer’s first.

“I vividly remember looking at this patient and thinking something isn’t right,” she said. “I couldn’t put my hand on what it was.”

The patient had come in for another emergency, but her vital signs just weren’t adding up, Singer said. She was also “walking and talking” and for the most part seemed fine.

“I would say my little alarm went off,” she said.

As Singer would soon learn, the patient had COVID-19.

“I think that was the turning point for everyone,” she said, explaining that’s when she and ER staff realized that some patients could, in fact, look mostly fine or be “walking and talking” and still have the virus.

“That’s what was scary about it,” Singer said.

As she went on to explain, a patient could have suffered a fall or dizzy spell and not really know why. Medical staff would then find his or her oxygen levels to be dangerously low.

Or a patient may have a cough and downplay its significance.

“So we may say, that sounds like a unique cough. How long have you had that,” she said.

Sometimes patients didn’t know or even realize they had the virus.

To make matters worse, COVID-19 began popping up around the southeast at a time when the region’s allergy season was only just getting started.

So Singer and the rest of the ER team had to “dig deep,” she said.

They learned not only to ask the usual questions, such as have you traveled lately or have you been exposed to someone who recently tested positive for COVID-19, but to pay attention to other symptoms and a patient’s all-important vital signs as well.

“You work as a team and you provide the care that’s seamless,” she said. “But to me, it’s not the ones who present with all kinds of the classic symptoms that’s scary. … It’s the ones who you have to think out of the box to figure out what’s wrong.”

Then there are the patients who are ill from the moment they come in, or who are sick and quickly worsen, both Singer and ICU nurse Candy Chappell said.

Patients like David Jackson who would be admitted first to the hospital, then to its intensive care unit where he would spend 11 days on a ventilator.

“When patients got to us they were pretty bad,” Chappell said, adding that many of the COVID-19 patients had similar symptoms: high fevers, respiratory issues with high oxygen requirements.

“We’ve all seen a lot of respiratory illnesses obviously, but you would see chest X-rays and you would say it looks typical for COVID-19,” she said. And a lot of patients would need to be intubated.

“And they needed to be intubated immediately,” she said.

That is when a tube is inserted into the patient’s throat and windpipe using general anesthesia. This is to make it easier to get air into the lungs. A ventilator then pumps in air with extra oxygen.

As one of the first patients to test positive and then be released from the hospital, David Jackson’s recovery was no small victory for the hospital, and one that would be celebrated with medical staff lining the halls and clapping for him as he was wheeled out.

But the road to recovery for patients like Jackson and the impact the virus has had on their families is difficult nonetheless, Chappell said.

When Jackson’s wife was informed she would not be allowed in with her husband, that’s when the gravity of the situation really hit them, Chappell said.

“That was the moment for me when I thought, ‘Oh my God. This is going to be terrible,’” she said. “I can’t imagine what I would do if that was my family and I couldn’t see them.”

To help ease her burden, Chappell brought her own phone in to Jackson’s room so his wife could FaceTime with him.

“It was very emotional watching them talk to each other,” she said.

The hospital eventually purchased and brought in iPads for patients to communicate with family members, but until then, Chappell allowed the couple to use her phone to check in. She’d also show Jackson’s wife his monitor to show her how well he was doing.

At some point, she told Chappell, ‘I think I can get some sleep tonight.’

Tragically, not all patients admitted to the ICU with the coronavirus make it.

“We want them all to do well and be successful and come off the ventilator,” Chappell said.

When they don’t, it is extremely difficult for family members who can’t be there with them, or hold their hand she said.

“Having them pass away and not be with their family, I think that’s the hardest part for us,” she said. “But it’s hardest on the families.”

Reluctant heroes

When the virus first hit Beaufort County, there was almost a feeling of, “Can this really be happening?” Chappell said.

“Just like everybody else we thought, ‘Surely it’s not going to come to Beaufort and bam, it was here,” she said.

Naturally, the medical staff was a little leery as many worried about taking the virus home to their families, she said. One only had to turn on the TV to see evidence of its devastation in places like New York or Italy, Chappell said.

“But we learned different things (to protect ourselves) as we went along,” she said, explaining that first staff would change out of scrubs before leaving work. Then later, they would change at home, stripping down in garages or exterior buildings, before going in to shower.

“But there was never any of thought that we were not going to take care of patients,” said Chappell, who hasn’t seen her own mother, 83, in over a month.

As many nurses including Chappell and Singer will tell you, they go into the profession out of a desire to care for others, even though the days can be long and sometimes emotionally or physically exhausting.

Both Singer and Chappell typically work 12-hour shifts, three times a week but can sometimes work an extra shift if needed. But both nurses also said it’s the medical staff and their own teams that make the difference.

“We have a very supportive group here,” Chappell said. “We all have a vested interest in these folks and when we don’t have a success, we talk about it and help each other through it.”

Singer echoed Chappell’s comments.

“We’ve gone through a lot together here,” she said, adding that when they’ve lost a patient, no matter what it’s from, it can be hard.

“We might close the doors to the trauma room, and just debrief,” she said. “And if you need a minute, there is a lot of respect where we work.”

Words like “hero” or “brave” are sometimes used to describe nurses, doctors, first responders and others on the front lines of the pandemic, but both Singer and Chappell were reluctant to call themselves heroes.

“I don’t feel like a hero,” Chappell said. “I feel like I’m doing my job, and I’m helping the community and doing what I need to do to help people, which is what I’m supposed to be doing.”

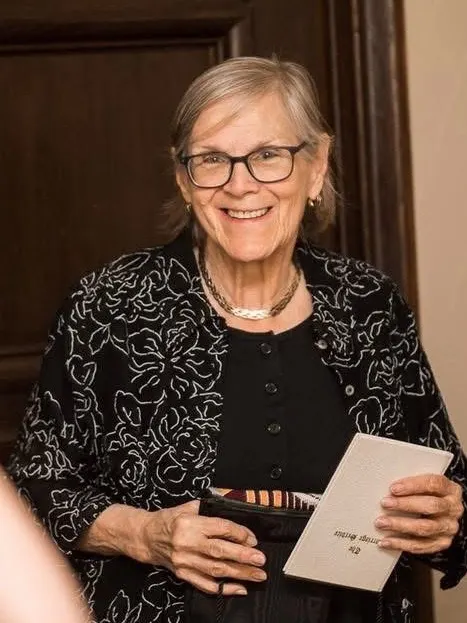

Nurses Lauren Singer (top) and Candy Chappell at work at Beaufort Memorial Hosptial. Photos by Mindy Lucas.