By Bill Rauch

The scientific community and the old-timers alike agree there’s seawater in Beaufort County in places there didn’t used to be.

Scientists, special interests and the politicians who represent the special interests argue over not whether the seas are rising — everyone agrees they are — but why the seas are rising.

This is the story of what is known about sea level rise in Beaufort County. There is nothing political about it … until the very end.

Charleston, our neighbor to the north, now experiences “nuisance flooding” an average of 23 days a year. That is, according to a recent National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) study, up roughly four times from what it was 50 years ago. Charleston is talking about a possible future need to erect barriers to the sea, and the city has already spent big money installing various check valves, pumps and water tunnels to help control the unwanted waters.

How fast is the land sinking and how fast are the seas rising here?

Both these factors are of course important and importantly, like the tides, they are not universal. The level of the ocean does not rise like a bathtub, oceanographers caution, and the land does not sink (what the scientific community calls “subsidence”) universally either, geologists say.

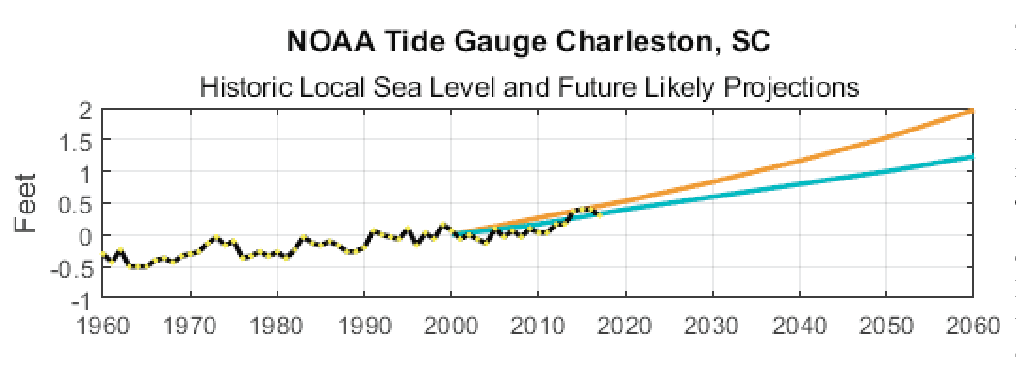

The NOAA maintains water level monitoring stations at the entrance to Charleston Harbor to our north and at Fort Pulaski outside Savannah to our south. The data from those facilities shows sea level rise plus land subsidence and confirms what the old-timers know: that between 1901 and 2017 the seas are higher at Charleston by an average of 3.25 millimeters per year, or by 1.07 feet per 100 years. The data from Savannah is similar: 3.24 millimeters per year with a 100 year total of 1.06 feet.

The NOAA maintains water level monitoring stations at the entrance to Charleston Harbor to our north and at Fort Pulaski outside Savannah to our south. The data from those facilities shows sea level rise plus land subsidence and confirms what the old-timers know: that between 1901 and 2017 the seas are higher at Charleston by an average of 3.25 millimeters per year, or by 1.07 feet per 100 years. The data from Savannah is similar: 3.24 millimeters per year with a 100 year total of 1.06 feet.

By way of comparison the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change recently released a report that says the worldwide average for sea level rise is 1.7-1.8 millimeters per year. Accordingly, keeping in mind that the seas do not rise like a bathtub and the land does not subside universally, these and other data indicate that the long term rate of sea level rise in the Lowcountry is about twice the global average.

Moreover, sea level rise here has quickened over the last decade, the Federal Government’s scientists say, and the quickening is expected to continue to increase here over the next 50 years.

“A slowing of the Gulf Stream, continued land subsidence, and gravitational changes from loss of land ice, especially in Antarctica, all will contribute to higher than global sea level rise amounts in this [the Carolina Lowcountry] area,” NOAA’s Dr. William V. Sweet said last week.

Sweet, a native of North Carolina, was the lead scientist for NOAA’s 2017 study, “Global and Regional Sea Level Rise Scenarios for the United States.”

At Charleston, NOAA’s reports predict, the rate of increase (sea level rise plus subsidence) over the next 50 years will be two to three times the previous rate, or 1.25-1.5 feet more lost to the sea by 2065.

With regular reports of Antarctic glaciers making unusual groaning sounds, and pictures of enormous icebergs freed from the polar ice cap, we are pretty well informed on the melting of the poles.

But little or nothing is said about subsidence.

That’s because subsidence is more local, and subsidence rates are affected by less understood influences than the melting of polar ice caps, influences like aquifer depletion and other subterranean events. Some coastal areas are subsiding virtually not at all while the subsidence rate elsewhere is dramatic.

Southwestern Louisiana is the most quickly subsiding area in the coastal U.S., according to U.S. Geological Survey maps. A recent Tulane University study found the land there is subsiding at twice the rate previously charted, or as much in some places as nearly half an inch per year. A recent Scientific American story attributed the dramatic subsidence increase there to offshore drilling.

Louisiana, a poor state where Big Oil holds big sway, has now permitted more than 50,000 wells in its coastal zone. The pipes that bring the crude oil ashore are laid into man-made undersea trenches that stretch from the rigs to the shore. Some scientists say the trench-digging contributes to the erosion of the land there. Others say the cavities left by the extracted oil result in undersea cave-ins, and that the collapses of these cavities contribute also to the unusual subsidence rate there. As can be easily imagined, the many and well-heeled proponents of Big Oil fiercely dispute any findings that lay increased subsidence rates at the feet of the oil companies.

Nonetheless, in addition to the very real, costly and destructive risk of spills, offshore drilling probably also causes beach denourishment.

Along the Florida to North Carolina seaboard the Carolina Lowcountry is already, in the words of Dr. Sweet, “in the subsidence bullseye” with subsidence rates of 1.3 millimeters per year. If we didn’t know it already, that tells us Beaufort County is a delicate place. And when the hurricanes come every millimeter counts.

All of that is why I’m going to do something next month that I rarely do. I’m going to vote for Joe Cunningham. I trust him way more than I trust his opponent to keep the rigs out.

Bill Rauch was the mayor of Beaufort from 1999-2008. Email Bill at TheRauchReport@gmail.com.